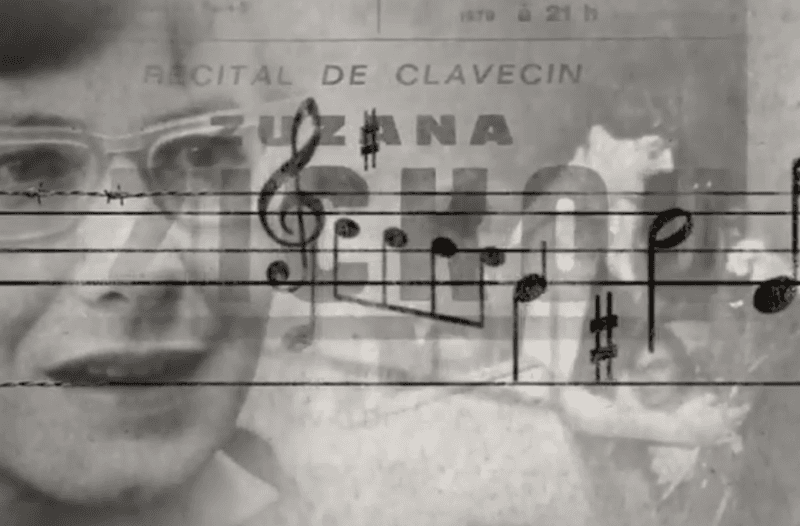

NEW YORK—Looking straight at the viewer, Zuzana Ruzickova, then 87, detailed the horrors of three Nazi concentration camps, and then the following communist regime takeover, in measured tones and with great clarity.

“When people ask me how I was able to survive, I always say, ‘It was a hundred miracles,’” Ruzickova said.