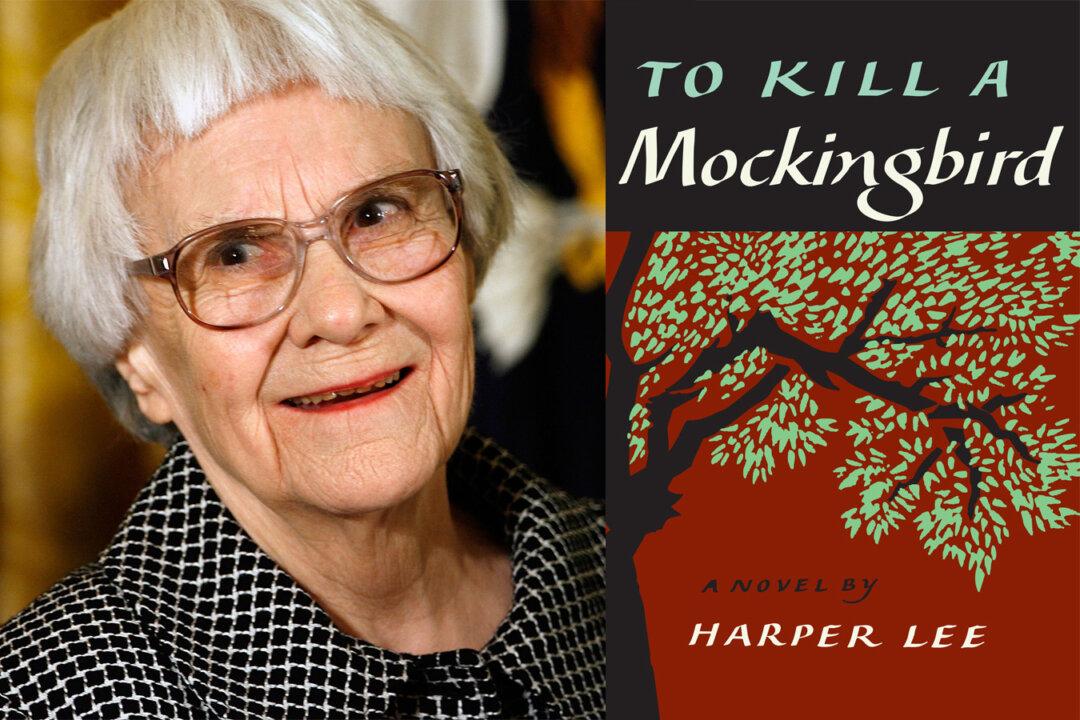

NEW YORK—Harper Lee has died, but the conversation about her life and work has only begun.

“I think the retrospective will be more useful than what was said during her lifetime, because there are a lot of things we can get down to that were impossible before,” Lee’s friend Wayne Flynt, an Alabama-based historian, told The Associated Press.

Lee’s death Friday at age 89 comes almost exactly a year after her publisher, HarperCollins, stunned the world by announcing that a second novel by the author of “To Kill a Mockingbird” would be released, ending what many believed was a permanent and much-desired literary silence.

[aolvideo src=“http://pshared.5min.com/Scripts/PlayerSeed.js?sid=1759&width=580&height=356&playList=519514368&responsive=false&pgType=console&pgTypeId=discovery-videoDetails-grabCodeBtn”]

With Lee confined to a nursing home in her native Monroeville, Alabama, and communicating only through press releases that many wondered if she even knew about, the debate about her state of mind and about the second book, “Go Set a Watchman,” took off without her. It will likely grow as those close to her finally speak up and more is learned about what, if any, other writings she left behind.

“Everybody from the newspaper boy to the checkout girl to the local minister will be remembering Harper Lee with fondness or with an ax to grind, depending on how they were treated,” said Lee biographer Charles Shields, whose “Mockingbird: A Portrait of Harper Lee” was published in 2006 and will be reissued this year.

Flynt is among those thinking about a memoir.

Lee’s retreat from public life over the past half-century created one kind of mystery; last summer’s publication of “Go Set a Watchman” started another. Millions who thought they “knew” Atticus Finch, who named their children for him and became lawyers because of him were faced with a seemingly different man in the new book, which took place 20 years later but actually had been written before Lee turned to what became “To Kill a Mockingbird.”

[caption id=“attachment_1970878” align=“alignnone” width=“674”] A pile of “Go Set a Watchman,” by Pulitzer Prize-winning Alabama author Harper Lee at a Books and Books store in Coral Gables, Fla., on July 14, 2015. (Joe Raedle/Getty Images)[/caption]

A pile of “Go Set a Watchman,” by Pulitzer Prize-winning Alabama author Harper Lee at a Books and Books store in Coral Gables, Fla., on July 14, 2015. (Joe Raedle/Getty Images)[/caption]The bold attorney who in the 1930s defended a black man accused of rape in “Mockingbird” had aged into a spiteful reactionary condemning the Supreme Court’s 1954 decision to outlaw segregation in public schools. Was the Atticus of “Mockingbird” a romanticized figure and the Atticus of “Watchman” closer to the truth? Did Atticus, based closely on Lee’s father, really change or was he simply a patrician more comfortable with the old rules, when all the powers belong to whites?

Ralph Eubanks, a former editor of the Virginia Quarterly Review and currently a visiting professor of Southern studies at Millsaps College in Jackson, Mississippi, said that the brilliance of “Mockingbird” was in how it could make anyone from the North or South identify with the issues and with the characters.

“For ‘Go Set a Watchman,” there was no one you were cheering for,“ he said. ”That for me changed the dynamic.”

In an email to The Associated Press, award-winning historian Isabel Wilkerson said that Lee had created two equally worthy legacies.

“Harper Lee has left us a great gift: a beloved vision of our better selves in ‘To Kill a Mockingbird’ and a thornier reflection of what lies beneath in her earlier manuscript, ‘Go Set a Watchman,’” wrote Wilkerson, best known “The Warmth of Other Suns,” which traced black migration from the South in the 20th century.

“In both, she has bravely given us versions of our country for us to ponder for generations.”

[morearticles]1970290, 1748292, 1463778[/morearticles]

James McBride, winner of the National Book Award in 2013 for the novel “Good Lord Bird” and author of the upcoming nonfiction “Kill ‘em and Leave” about James Brown, said reading “To Kill a Mockingbird” as a child made him want to become a writer and that it “crystallized” for him an awareness of racism that had been “floating around him.” Nobel laureate Toni Morrison and others have labeled the book a “white savior” novel, but McBride believes that “Mockingbird” is the best story that Lee could have told.

“Yes, I would have liked to see the black characters displayed with a lot more dimension,” he said. “But Harper Lee gave it all she had. She left nothing behind, and that’s all you can ask for.”

McBride has re-read “Mockingbird” a few times, catching new and important details with each reading, and has given the book to his kids, too.

He has not read “Go Set a Watchman.”

“I prefer to remember ‘To Kill a Mockingbird’ and Atticus Finch and all those characters as Harper Lee wanted us to remember them. I believe she wasn’t strong enough at the end of her life to make any informed decisions about her work,” he said.

“There is no question in my mind that Harper Lee is a great American writer with the best of intentions. You have to start the conversation about race somewhere, and Harper Lee is a great place to start it.”