Part of the genius of Shakespeare’s “Hamlet” is its unflinching look at the ultimate questions of human life, questions about death, doubt, and faith. One way Shakespeare enhanced those themes was through imagery associated with Ash Wednesday and Lent that runs through the work. Using this imagery, Shakespeare draws readers into an atmosphere colored by sin, penance, death, and what follows it.

The Religious Background

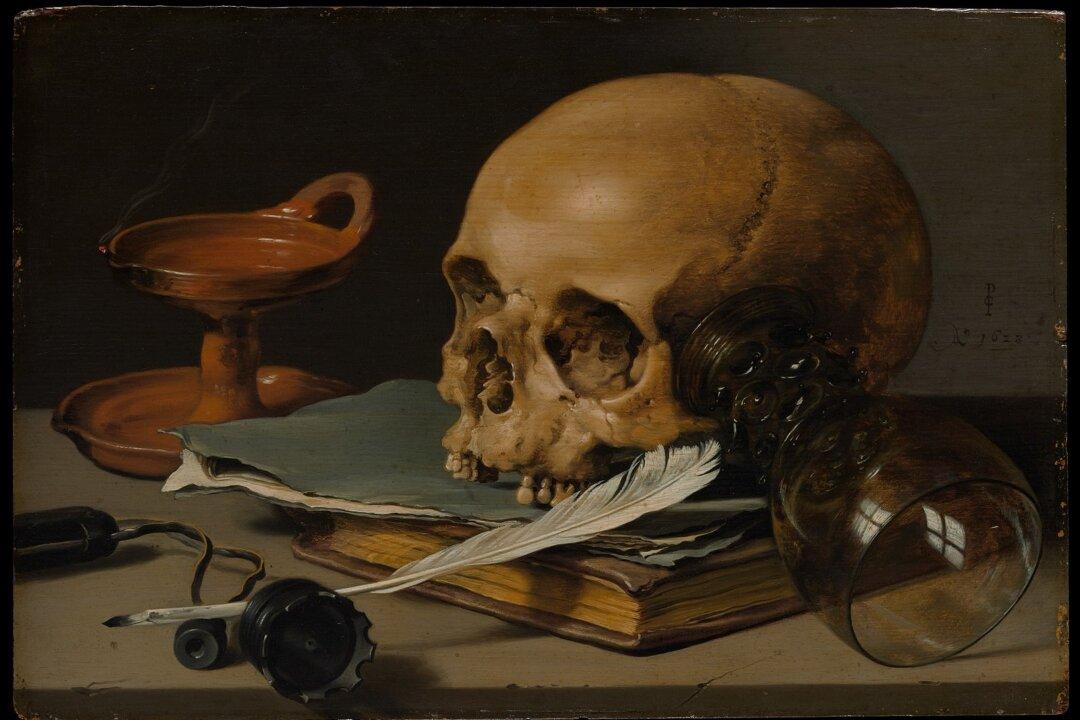

In the Christian tradition, Lent is a time of fasting, penance, prayer, and self-denial offered to God in reparation for sin and to achieve spiritual cleansing. This penitential season is also a preparation for Holy Week and Easter. It begins on Ash Wednesday and ends 40 days later, excluding Sundays, on Easter Sunday. Lent is meant to mirror Christ’s 40-day fast in the desert.Traditionally, the Ash Wednesday liturgy includes a rite during which the people kneel and receive ashes on their forehead in the shape of a cross. During the rite, the priest or minister recites over the penitent these words: “Remember that thou art dust, and to dust thou shalt return.” Thus the Lenten season is inaugurated with ashes, an ancient symbol of penance and a reminder of death, a “memento mori.”