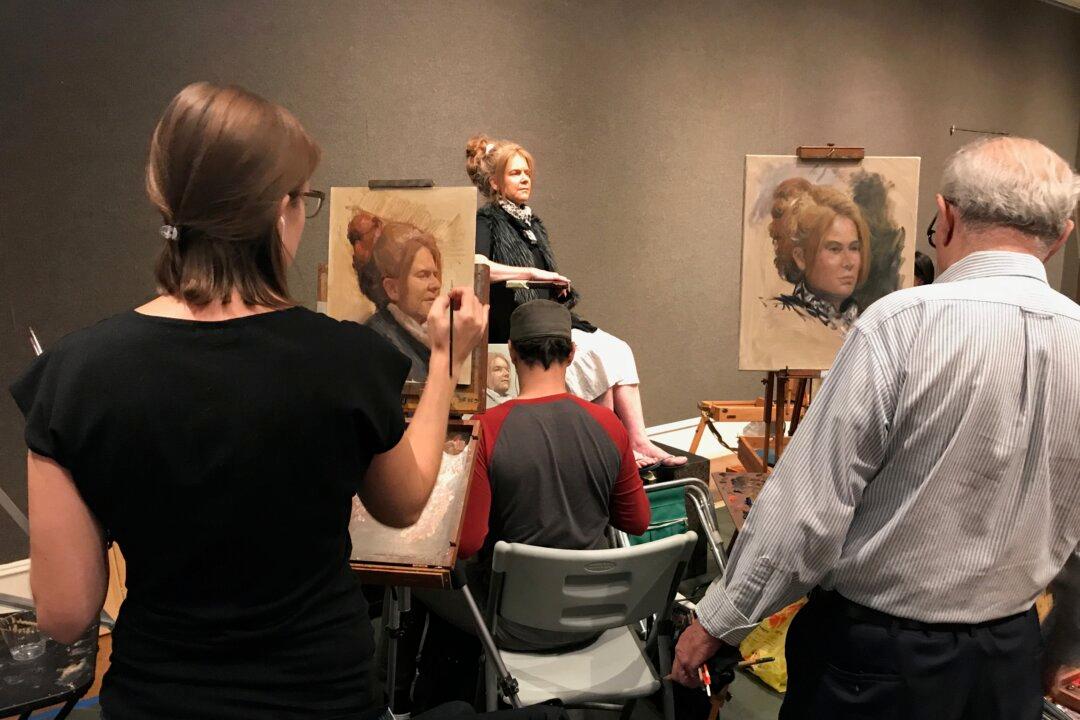

NEW YORK—The smell of oil paint filled the room. It was so quiet, you could hear the rustle of paintbrushes as 40 artists painted shoulder to shoulder in the main gallery of the Salmagundi Club.

The painters had 3 1/2 hours—split into 20-minute sessions punctuated by 5-minute breaks—to complete a portrait. Their collective sense of focus was almost palpable. The rhythm of them stepping to and fro at their easels to see their paintings in progress would occasionally ease the pressure, until the organizer, Salmagundian and painting conservator Alexander Katlan, finally announced, “Three minutes left!”