WILMINGTON, Del.—Michael J. Emmons Jr. stalks historical graffiti, the tags of time that might tell a story, rather than precious artifacts you would expect to interest a historian like him.

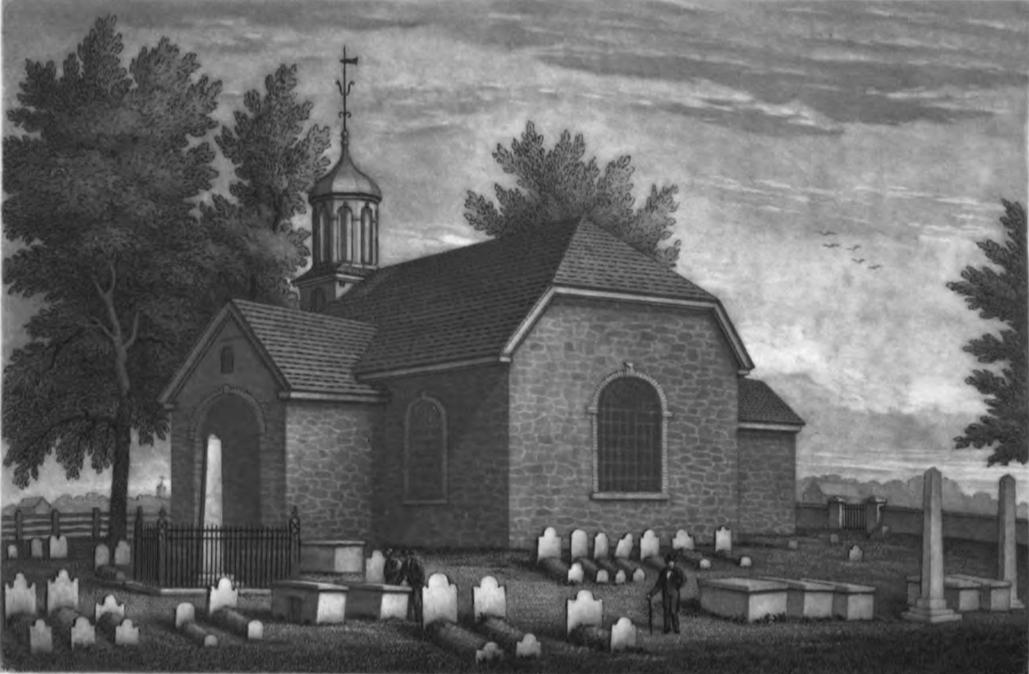

At Old Swedes Church in Wilmington, he is more fascinated by the 17th century wooden doors, pockmarked with hundreds of crudely carved sentiments, names, drawings and dates, than he is the black-walnut pulpit inside the 1698 church founded by Swedish settlers or its Bayard memorial stained-glass window, one of the first made by Tiffany.

They are lovely. But it’s these scratched words and pictures, so many that the surfaces are in danger of looking more like big wooden school notebooks than entrances to a church - that command Emmons’ attention.

“It’s kind of a poignant thing to encounter, when you see these signs people left you a couple of hundred years ago,” Emmons says. “Just on an emotional level, I think it’s fun to find them.

“On a scholarly level, these things are telling us a lot that can help us understand American history, help us understand architectural history and how they used buildings, what they tried to say with their buildings. It helps us understand how people related to things, the material world and their experiences in dwellings and churches. It helps us better understand people and society and their culture.”

Emmons may not have Indiana Jones’ fedora and whip, but he’s is a treasure hunter just the same. His gems and jewels, though, come in the form of historical markings on old buildings, whether it’s a formal cornerstone, a builder’s mark, etchings in stone, wood or glass—or all manner of writing and carving.