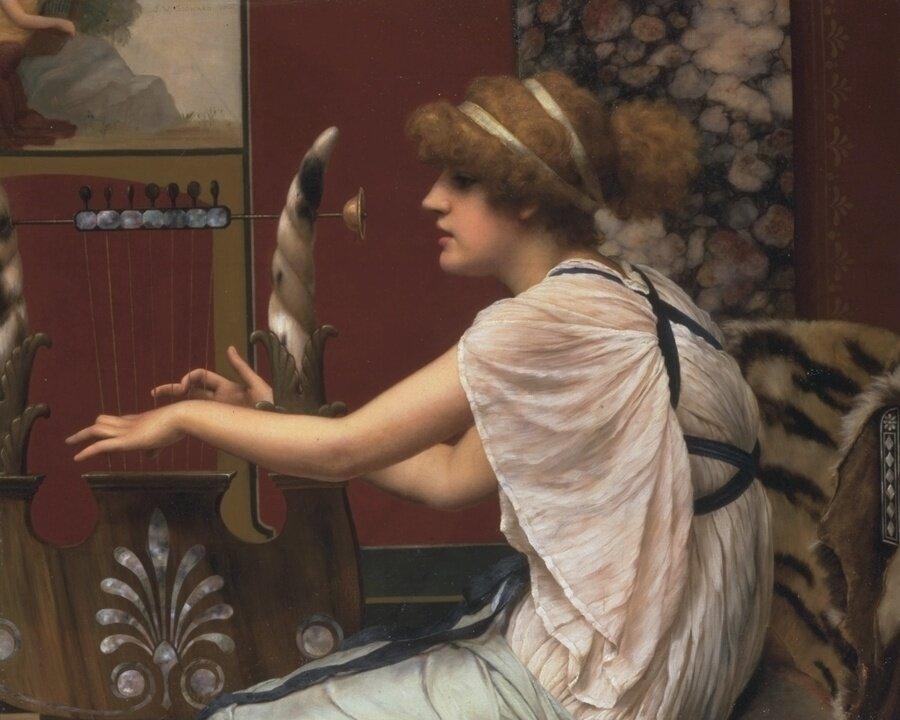

Both of Homer’s monumental works of poetry, The Iliad and The Odyssey, began by invoking the Muses.

Muses can be seen flanking Rome’s greatest literary figure, Virgil, in mosaic tributes to the master.

Both of Homer’s monumental works of poetry, The Iliad and The Odyssey, began by invoking the Muses.

Muses can be seen flanking Rome’s greatest literary figure, Virgil, in mosaic tributes to the master.