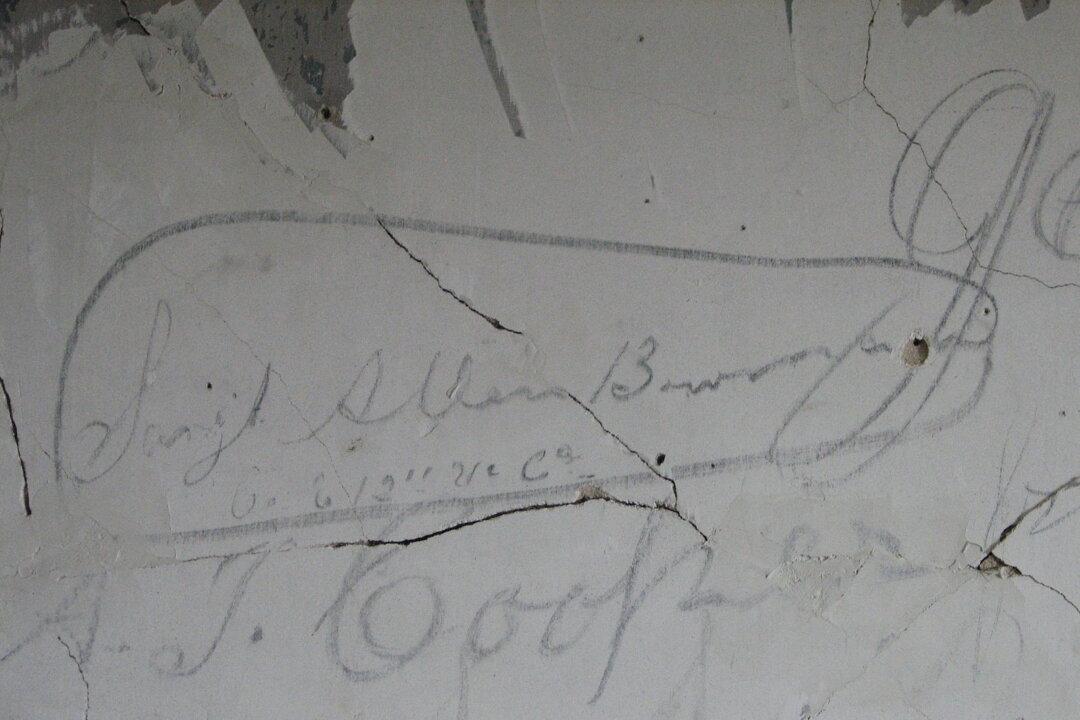

Rolling through the rural backroads of a 180-mile stretch from Gettysburg, Pennsylvania to Charlottesville, Virginia, referred to as the “Journey Through Hallowed Ground National Heritage Area,” drivers might zip by what seems like just another of the innumerable 19th-century clapboard houses on that route. Yet, on Brandy Road in Brandy Station, Virginia, population around 200, a house built around 1858 holds historical significance because of the words written on its walls.

The Graffiti House was a Civil War field hospital in Brandy Station, Va. It's the site of hundreds of soldiers' signatures. Cecouchman/CC BY-SA 3.0