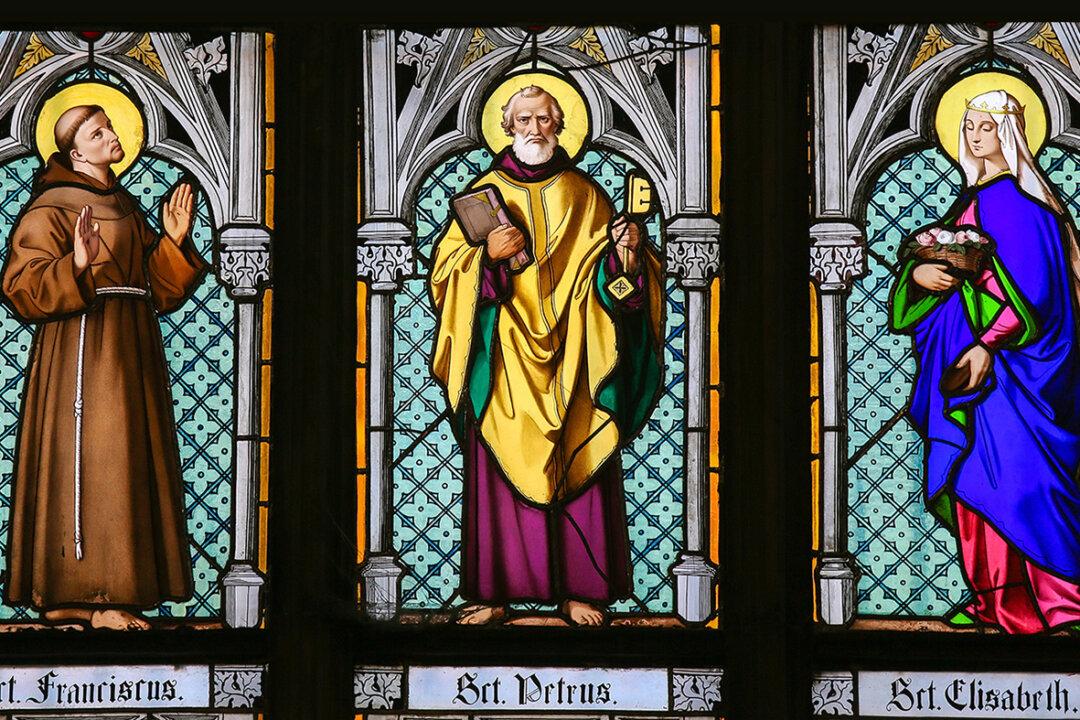

Enter a Catholic or Orthodox church, visit certain art museums, open a book of Western paintings, or search online for “paintings of saints,” and you’ll find portraits and scenes in paint or stained glass of men, women, and children recognized for their holiness.

These saints are often depicted in quiet prayer or devotion, the palm of one hand over their heart, their gaze turned toward heaven. Some are shown working miracles, like Reubens’s painting of Ignatius of Loyola or Tintoretto’s “St. Mark Working Many Miracles.” Martyred saints may be depicted at their execution accompanied by the instruments of their torture; these canvases are sometimes almost unbearably gruesome.