For as monumental a figure as George Washington was, the first president of the United States was acutely aware of his personality imperfections. His commitment to doing something about it, though, just proves how dedication to self-improvement can seriously get you places in life.

An Unmannered Youth

Born to Augustine Washington, a well-to-do but not extremely wealthy tobacco plantation owner, George was not part of high Virginian aristocracy. Unlike his older brother Lawrence Washington, who attended Appleby Grammar School in England, George was neither sophisticated nor well spoken. That would improve somewhat, thanks to some early intervention, but he would remain self-conscious of his lowborn manners for some time.

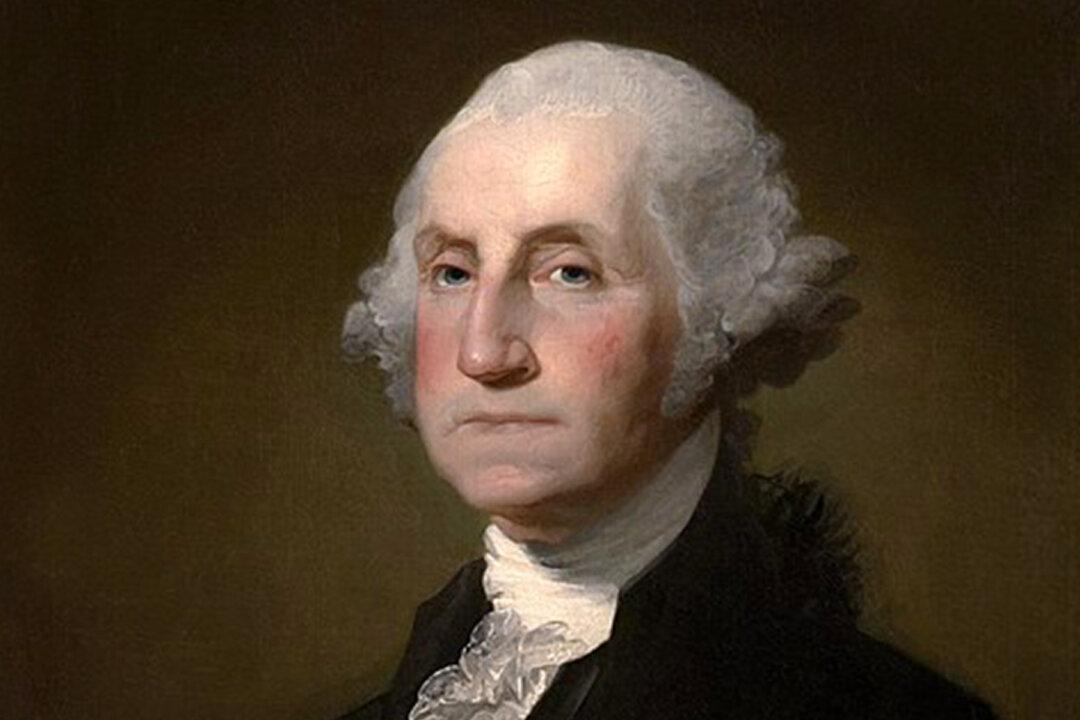

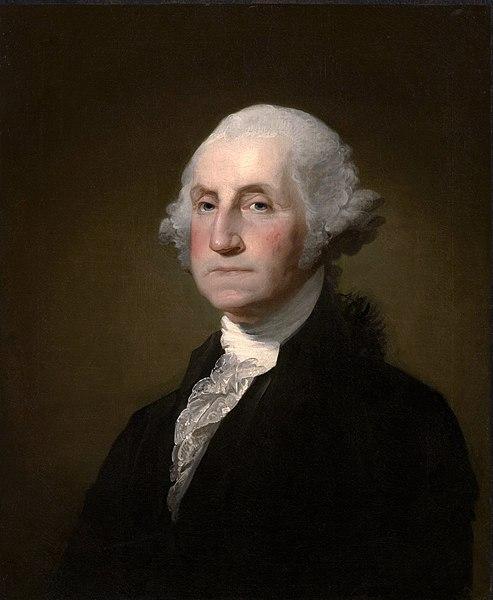

Gilbert Stuart, George Washington, 1797. Gilbert Stuart/Wikimedia Commons