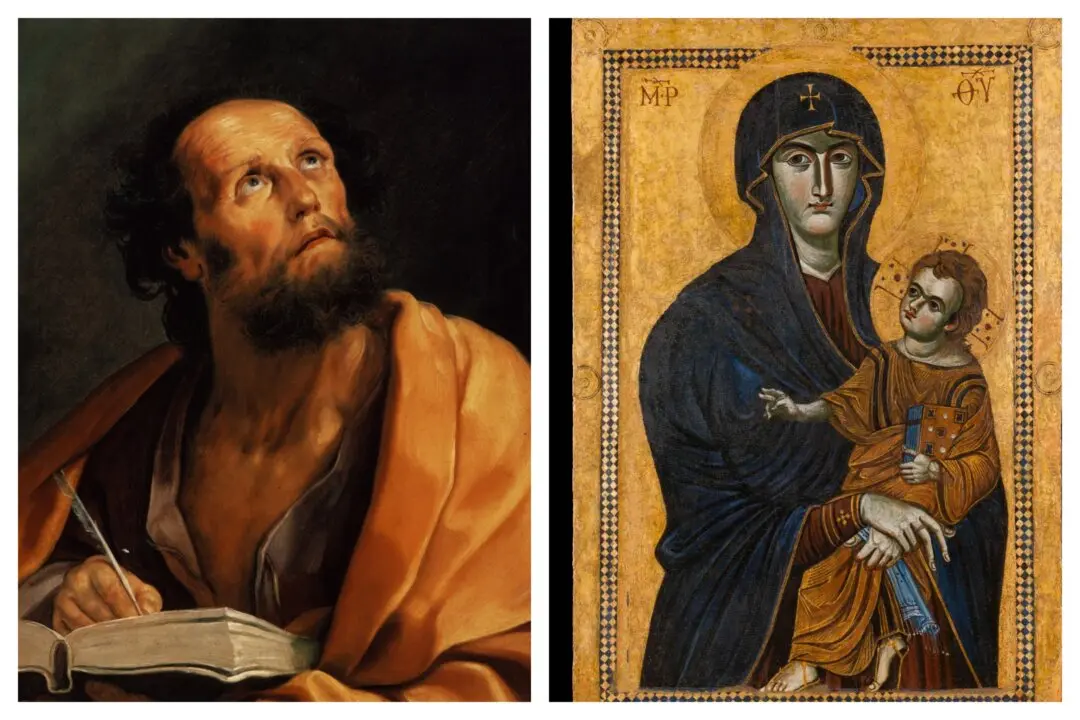

“Our hearts are restless until they rest in you,” wrote St. Augustine. Over 1,000 years later, George Herbert wrote a poem giving us the backstory as to why this is so.

George Herbert lived from 1593 to 1633 and was one of the metaphysical poets who wrote in 17th-century England. I defer to the wisdom of T.S. Eliot, who said that metaphysical poetry is extremely difficult to define but generally is characterized by the use of conceit, which is an extended metaphor, and reflections on the invisible reality.