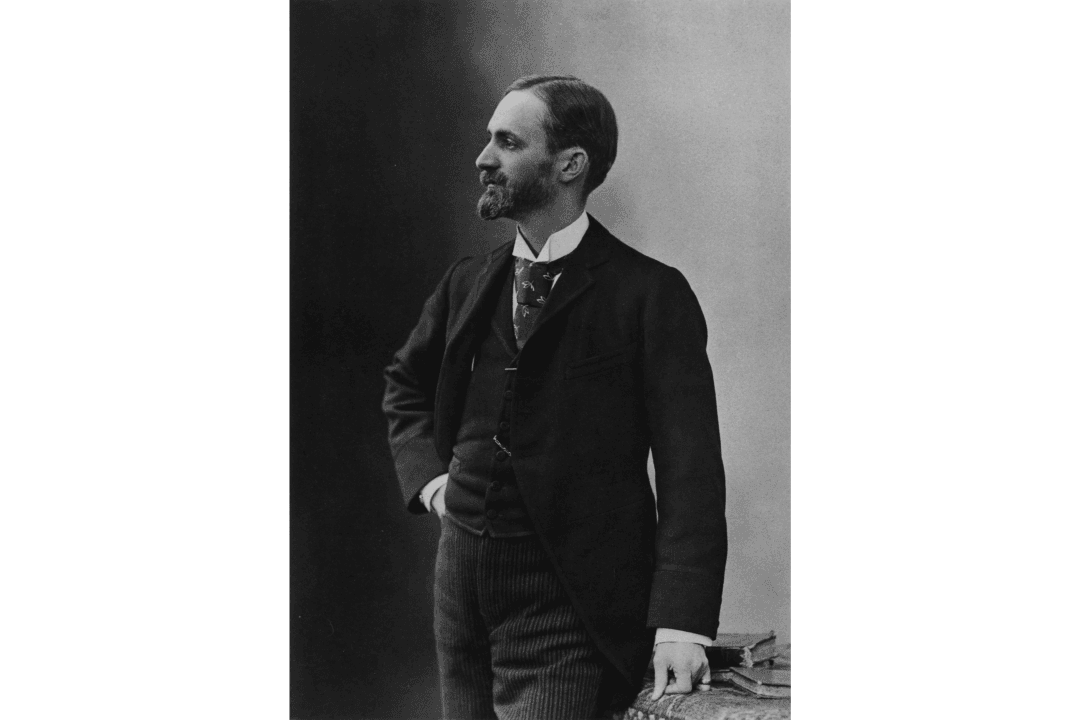

Born in the small town of Waterville, New York, George Eastman (1854–1932) soon moved with his family to Rochester, where his father, George Washington Eastman, had begun a business school called Eastman’s Commercial College. Along with running the school, the elder Eastman sold fruit trees and flowers to help make ends meet for his wife and three children.

After the family was in Rochester for two years, George Washington Eastman suddenly died. The college closed and the family was left in dire financial straits. His mother, Maria, somehow managed to keep the family together, despite the middle child, Emma Kate, suffering from polio.