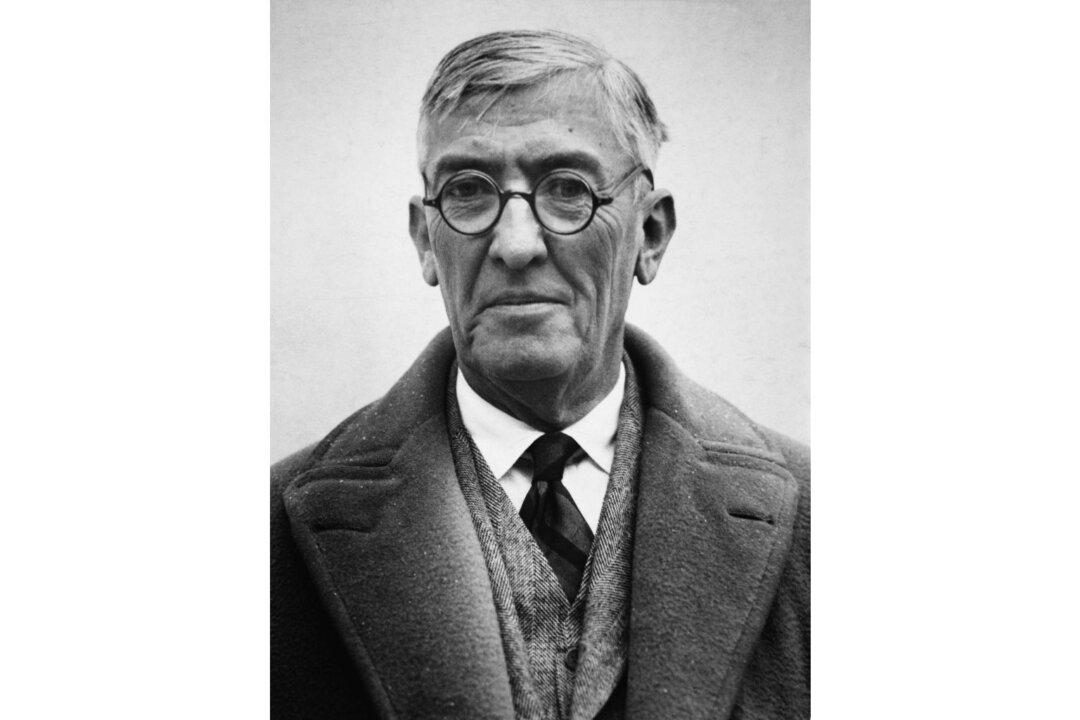

It’s not every day that a writer is compared to Aesop, the author of Greek morality tales, and to Mark Twain, the famed humorist and writer. Such was the reputation of Indiana native George Ade, a newspaper columnist, humorist, and playwright who achieved huge commercial success in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Like Twain, George Ade (1866–1944) saw humor in the human condition. He possessed a natural talent for communicating human foibles in a genial and lighthearted voice, as if he was sharing a wink and good-natured chuckle with his reader. He not only wrote about the average working man in a friendly way, but he also “talked their talk” by seasoning his work with the vernacular and slang of the common man.

Endowed with the same ethics and principles as many Midwesterners, Ade began including morals in his humorous stories. They only increased his work’s popularity. This quickly gained him fame, wealth, and national exposure as a compelling storyteller and humorist.