High school history books and even modern pop culture tend to focus on one key aspect of Civil War Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman’s life: The fact that he led the 1864 March to the Sea that resulted in Atlanta losing around 40 percent of its infrastructure to fire. A T-shirt sold at the 1996 Atlanta Olympics even featured Sherman’s image against flames and the message: “Atlanta’s Original Torchbearer.”

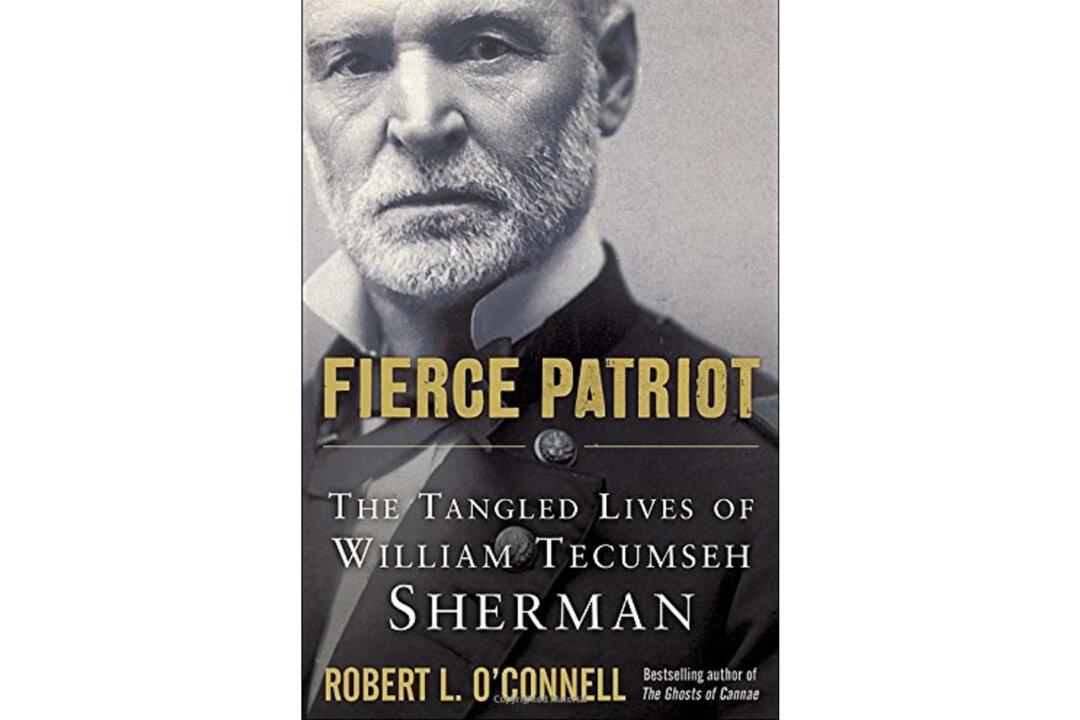

However, Sherman was a complex character with manifold personal interests, according to history professor Robert L. O’Connell in his book “Fierce Patriot: The Tangled Lives of William Tecumseh Sherman.”