The Gateway Arch majestically dominates the skyline of St. Louis, Missouri, and has come to symbolize the great city in the heartland of America. Reflecting St. Louis’s role in the nation’s westward expansion, the monument was constructed to memorialize the few hearty souls that set out to explore a new frontier. Thomas Jefferson sent his close confidantes Meriwether Lewis and William Clark on an epic excursion from the cultivated hills of Virginia to the country’s newly purchased and unchartered Louisiana territory. In the early 19th century, the shores of the Mississippi represented no less than the beginnings of a journey to “the ends of the earth.”

Architect of the Arch

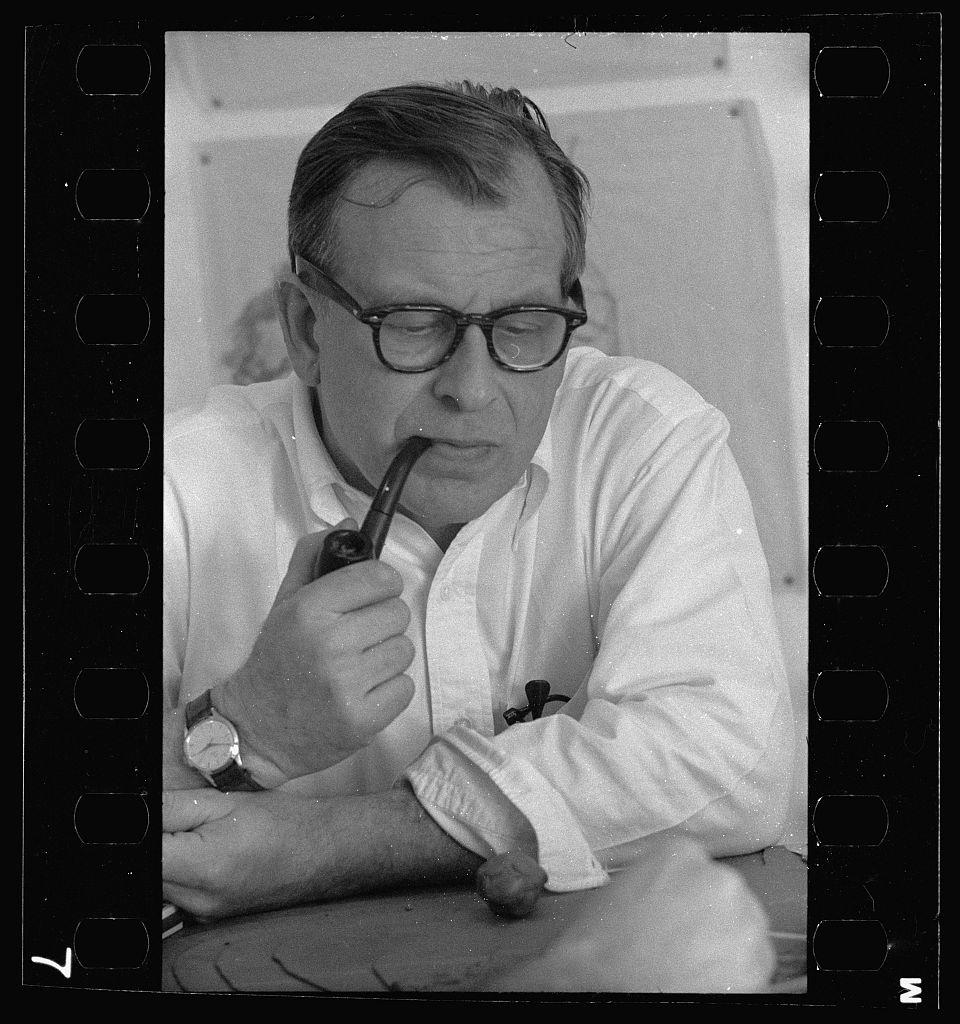

Architect Eero Saarinen, circa 1955. Library of Congress. Public Domain