David Amram is a difficult musician to classify, frequently blurring the distinctions between jazz, classical, and world music. He has also composed scores for several memorable films including John Frankenheimer’s Manchurian Candidate,” Elia Kazan’s Splendor in the Grass, and Robert Frank’s Pull My Daisy,” featuring the “narration” of Jack Kerouac.

Given his past collaboration with Kerouac and experimentation with world music, it is not surprising Amram had a strong affinity for T.C. McLuhan’s new documentary The Frontier Gandhi: Badshah Khan, a Torch for Peace, which had its American debut at the Indo American Arts Council’s Film Festival last Saturday, which was followed by a special concert performance by David Amram himself.

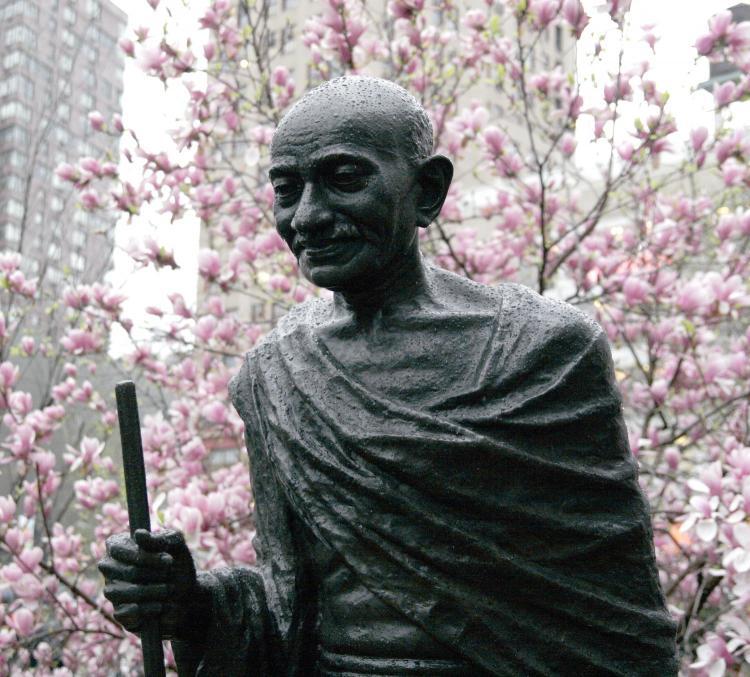

McLuhan’s documentary reverently tells the story of Ghaffar “Badshah” Khan, Mahatma Gandhi’s Islamic contemporary and close colleague in their campaign for Indian independence. Khan’s early advocacy of non-violence is presented as a remarkable development, since he was a devout Muslim Pashtun from what was then Northwest India, a region long associated with war and strife—think of the Khyber Pass. As Frontier explains, both men developed similar non-violent ideologies separately, but joined forces to become the “Odd Couple” of the Indian independence movement. One was short and Hindu, the other was tall and Muslim.

As a native of the North-West Frontier Province, independence did not exactly work out the way Khan had hoped, eventually finding himself a resident of Pakistan following the national referendum of 1947. Frontier is strongest when addressing Khan’s post-independence years in the wilderness, when he was all but forgotten in India and unwelcome in Pakistan, spending most of his time in Afghanistan. Unfortunately though, Frontier never truly gives a sense of who Khan was on a human level, ultimately becoming an exercise in hagiography.

Great effort clearly went into the making of Frontier, including interviews with Afghan President Hamid Karzai (who also happens to be Pashtun) and then Pakistani President Pervez Musharraf. Amram’s music is quite tasteful and appropriate throughout. Featuring the great Badal Roy on tabla, it incorporates his world and classical chops, but jazz is not an appreciable part of the compositional mix. However, his concert afterward would be a different story.

Amram developed a special program integrating music from around the globe, with an unusual quartet of Avram Pengas on either guitar or Greek bouzuki, his son Adam on congas, and daughter-in-law Teresa Colamonaco on tambourine (an instrument Amram spiritedly defended at one point), with the leader on just about everything else. He started on flute with a raga dedicated to Roy, before shifting to piano for a slow blues.

Amram had a plethora of exotic instruments spread across the stage for pieces dedicated to various forms of traditional music, including the shanai and dumbek representing Egypt, the Lakota flute for a piece originally composed for the Philadelphia orchestra, and a surprisingly bluesy number featuring the bouzuki and traditional Chinese woodwind. However, the highlight of his set was a rendition of a jazz waltz he composed for a production of Arthur Miller’s After the Fall, which he started at the piano, but concluded playing two penny whistles simultaneously, Rahsaan Kirk-style.

Amram performed a great set, clearly inspired by McLuhan’s preceding film. As for the documentary itself, Frontier is at times informative, but its over-awed tone will limit its appeal to those who already share the filmmakers’ veneration of Khan.

Joe Bendel blogs on jazz and cultural issues at http://jbspins.blogspot.com/ and coordinated the Jazz Foundation of America’s instrument donation campaign for musicians displaced by Hurricane Katrina.