On the far reaches of the Pacific Coast, atop the craggy rock face of the Ocean Beach coastline sat the Cliff House. It had been built originally in 1863. The ornate, though relatively small resort was built for wealthy patrons, and, in the Golden State, there were plenty of such patrons. The original location survived until it was engulfed in flames on Christmas Day 1894. Six months later, the millionaire Adolph Sutro made plans for its renewal, but with a much grander vision. It opened in 1896 as a Victorian style castle-like resort, boasting eight-stories of bars, parlors, dining rooms, a photo and art gallery, and an unparalleled view of the Pacific Ocean. As Christmas Day in 1902 neared, patrons could no doubt witness the unfolding of one of the most significant events in the history of communication.

From San Francisco to Honolulu: The Story of the Transpacific Cable

In ‘This Week in History,’ naval soundings in the Pacific, the annexation of Hawaii, and the defeat of the Spanish forever changed the way we communicate.

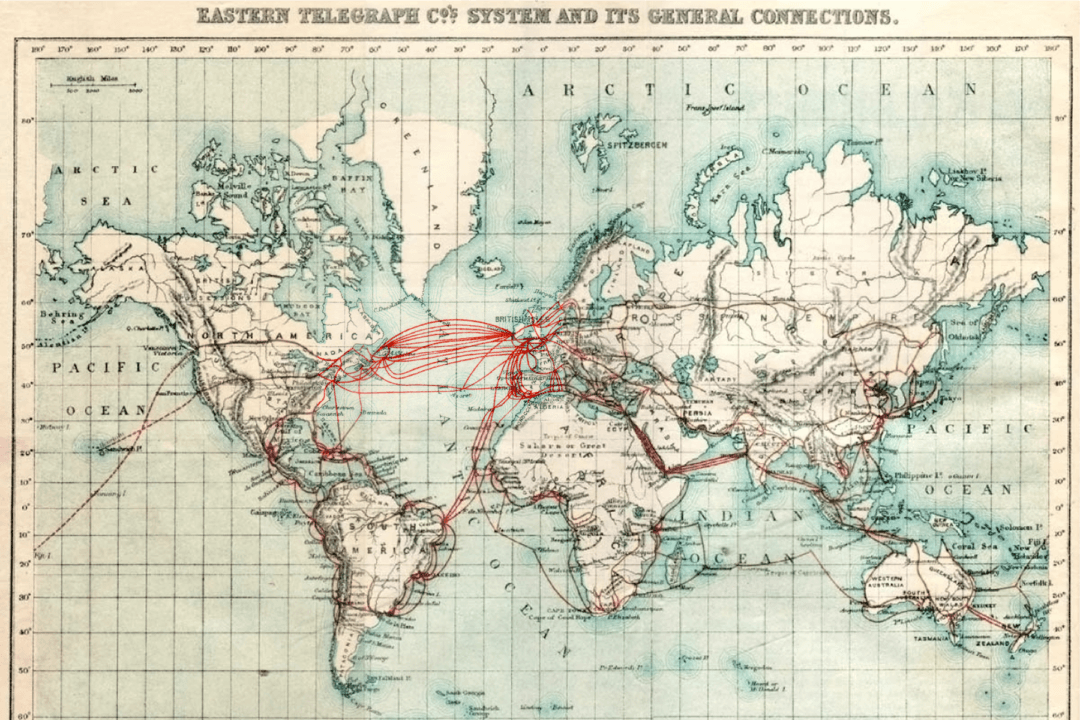

Eastern Telegraph Company network in 1901. Public Domain

Along Ocean Beach and just south of Cliff House, approximately 40,000 people gathered to celebrate the final step in the telegraphic interconnectivity of the entire globe.