ADDIS ABABA, Ethiopia—The opening of Ethiopia’s once-secretive imperial palace complex has been hailed as symbolizing a new era of openness for the East African nation, but it also has another aim—job creation.

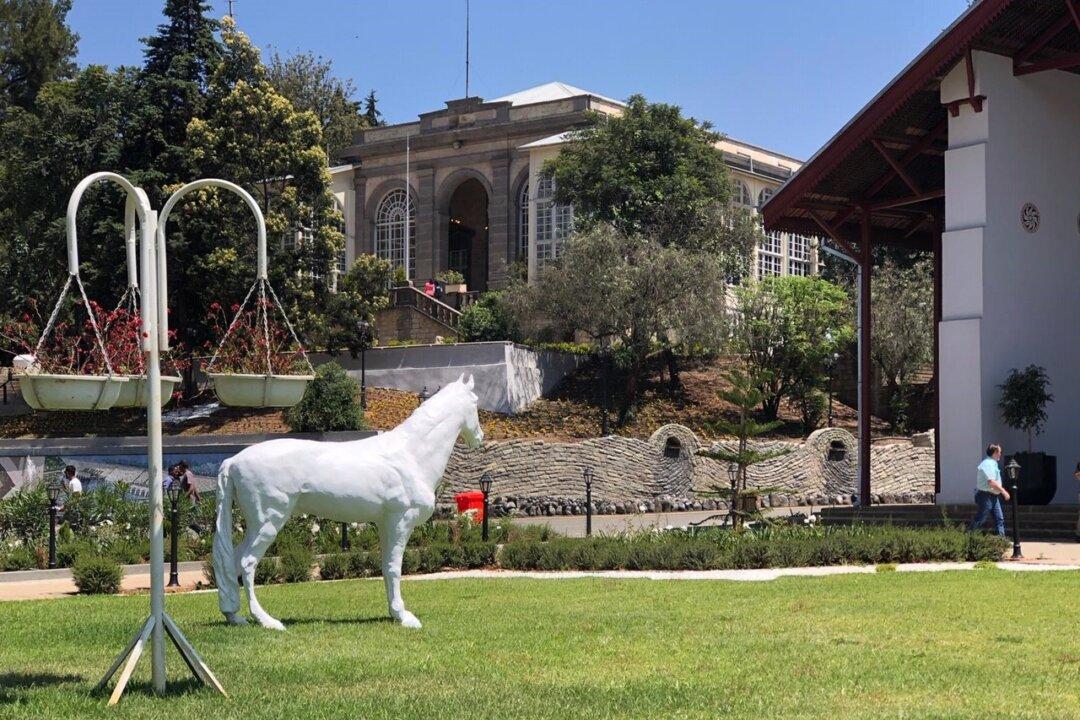

The Menelik palace and its 40-acre Unity Park compound overlooking Addis Ababa opened to the public in October after being closed for more than a century when it housed emperors, but was also used as a torture site under the communist Derg regime.