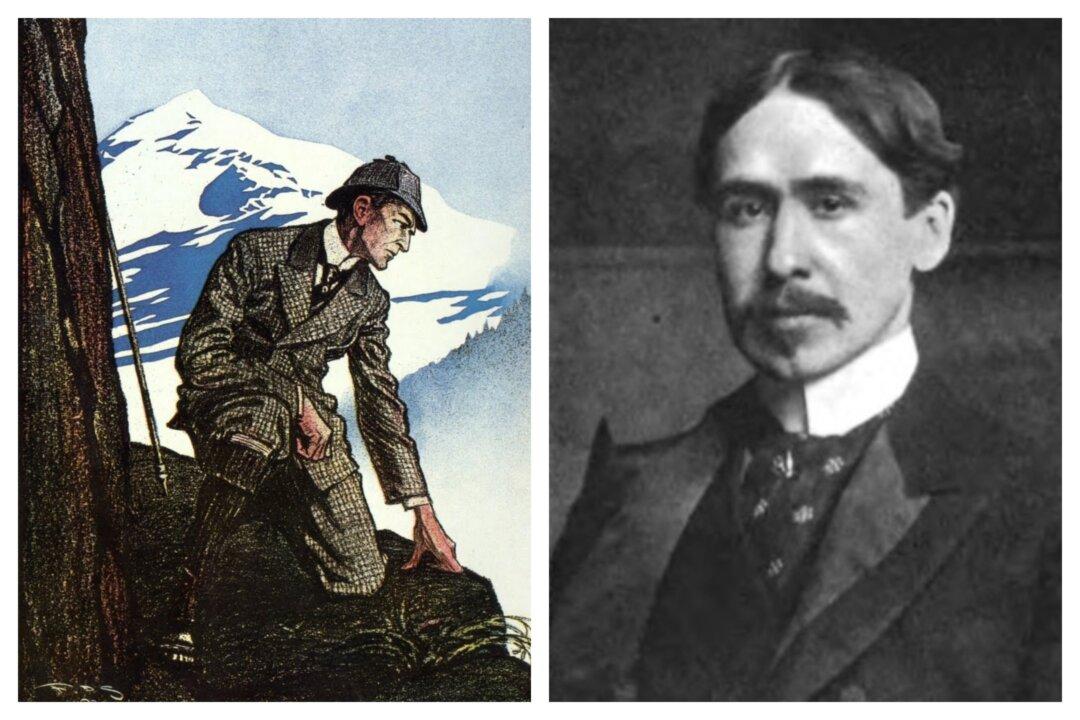

Artistry obviously ran through the veins of Frederic Dorr Steele (1873–1944). His grandmother Julia Ripley Dorr made her name as a novelist and poet. Her sentimental poetry was well-received, and she became friends with some of the country’s most prolific poets, including Oliver Wendell Holmes and Ralph Waldo Emerson. Emerson actually published her poem in his 1874 anthology “Parnassus.”

Zulma Dorr Steele, the daughter of Julia and mother of Frederic, though not a professional, was a fine artist in her own right. When Scribner’s Magazine published Julia’s poetry, Zulma created illustrations for it. It was the art of illustration that Frederic would eventually pursue.