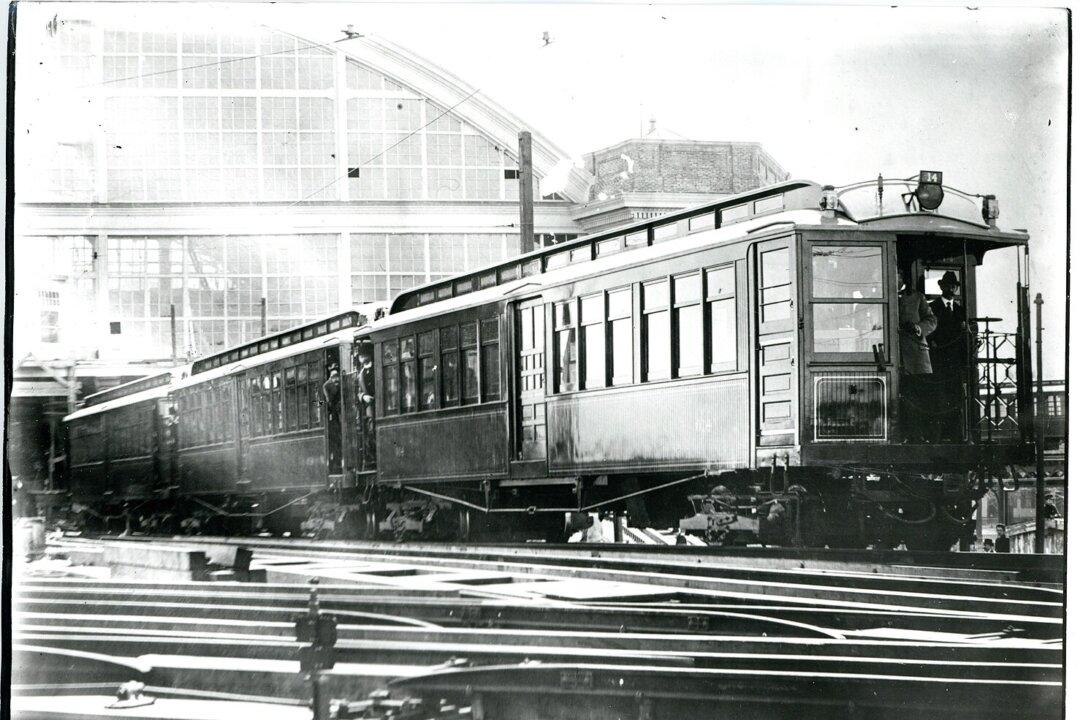

The power of steam transformed the transportation of people and goods, but with it came soot, smoke, and pollution. As cities grew and rail systems expanded above and below ground, the world desperately needed a new source of power. Frank Sprague’s invention soon revolutionized travel around the globe.

Early Railroad Days

Three decades before Frank Julian Sprague (1857–1934) was born, the city of Quincy, Massachusetts opened America’s first railroad. It wasn’t powered by a steam engine, however. Rather, the cars were pulled by horses on a three-mile track. The use of rails made horsepower more effective, but it was still slow going. In 1830, the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad became the first steam engine operation and the method of travel and commerce was forever changed.When Sprague was 5 years old, London opened the world’s first subway. It completely transformed inner city travel, but these underground trains were similar to those above ground, since they were steam-powered. The soot, smoke, and air pollution made traveling underground unappealing. Sprague, an inquisitive child, would grow up to change above and below-ground travel.