LIVINGSTON, N.J.—Looking out of his office window, Rabbi Zalman Grossbaum finds it hard to get work done as he watches kids enjoying the miniature town he built for them.

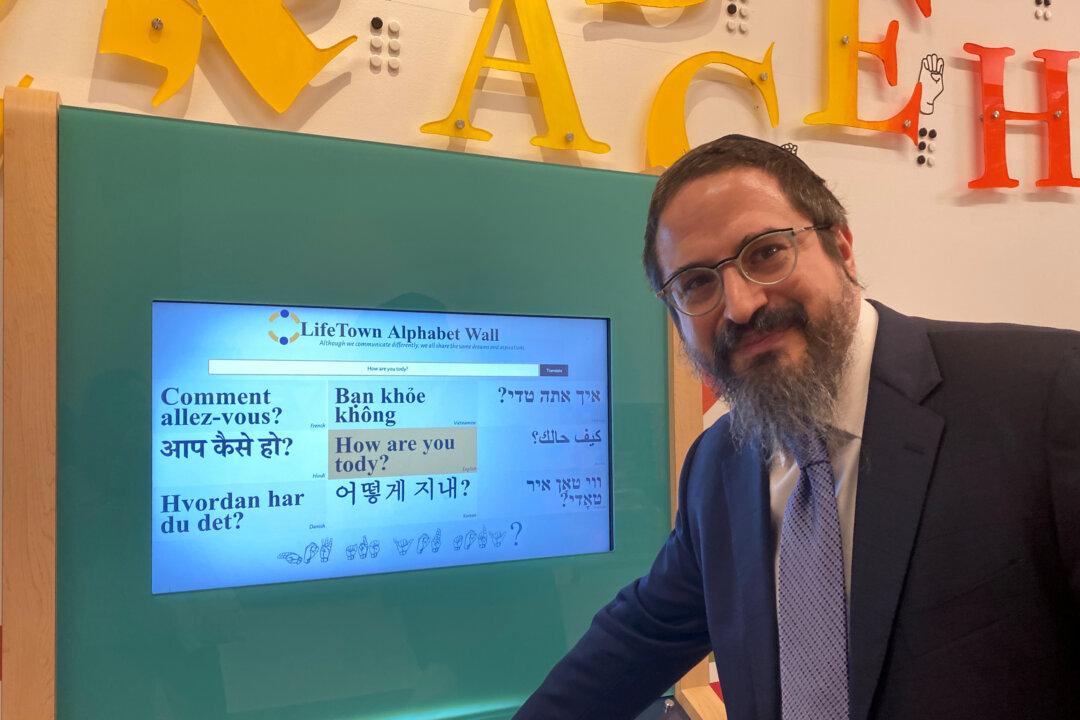

The village of storefronts inside his enclosed “LifeTown” complex in Livingston, New Jersey, lets children with special needs—“special abilities,” Grossbaum insists—hone their social skills, and he always wants to join them.