Sambal is a hot relish that originated in Java, Indonesia. There are thousands of versions across the archipelago, and sambal can also be found in Sri Lanka, Malaysia, Singapore, and Brunei. The term derives from the Javanese word sambel, meaning “condiment,” and for most Indonesians, a meal is not complete without it.

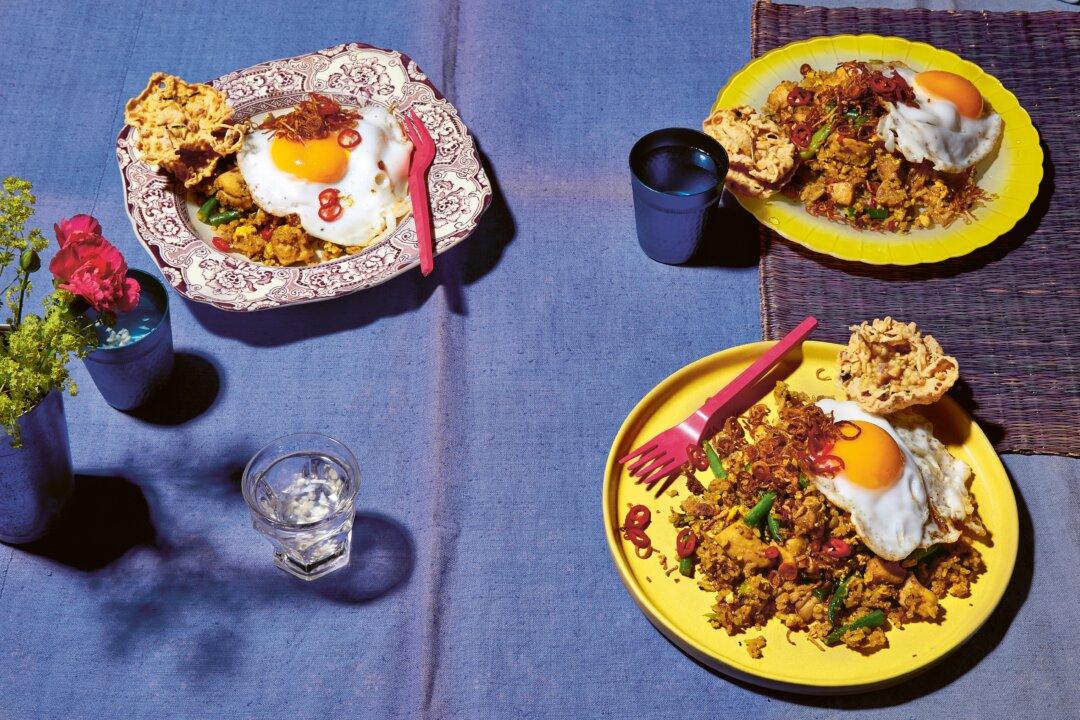

Nearly every meal is built around sambal, which is placed in the center of the table along with rice and kerupuk crackers; meat, fish, and vegetable dishes surround sambal as supporting acts, rather than the main event.