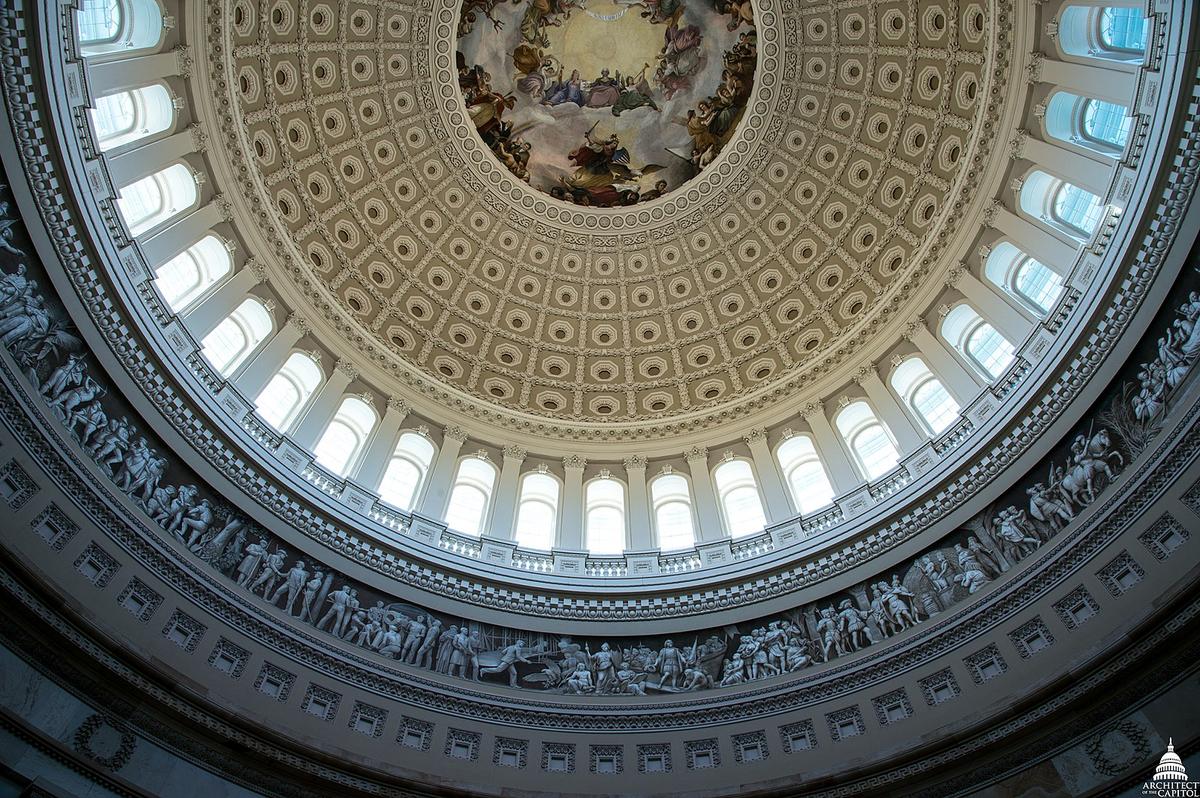

So much is viewable while standing inside Washington’s Capitol rotunda. Many consider the visual experience of the domed circular room overwhelming. Yet, it’s easy to overlook important historical significance unless visitors spend time studying the art, architecture, and sculptures in this vast space. Such is the case with the rotunda’s frieze.

A partial view of the Capitol rotunda's frieze, which wraps around the interior of the building. Public Domain