NR | 1h 44min | Documentary, Health, Medical | 2023

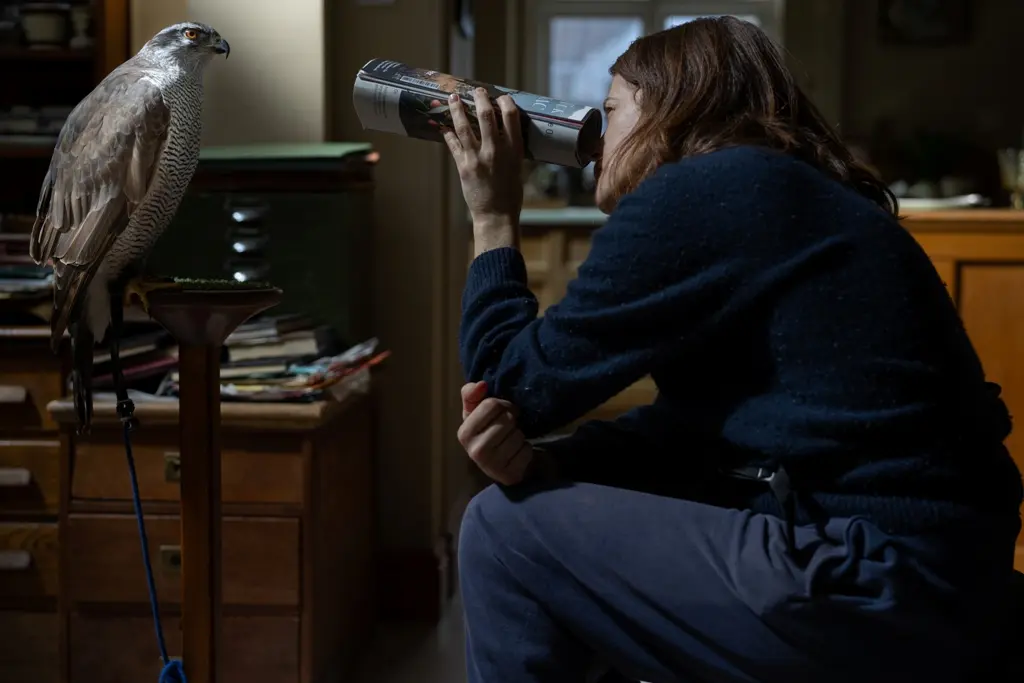

Right up there with death and taxes, every American is more than likely to visit a hospital during their lifetime; most of us, multiple times. There was a point in our nation’s history when, whether you lived in a large metropolitan area or the tiniest of rural hamlets, emergency, prenatal, and preventive care was no more than a short drive away.