Abigail Adams has been lauded by historians and at least one president, Harry Truman, for her grit and keen insight. As the second of the first ladies, Abigail experienced firsthand the fight for a nation and the establishment of America. In fact, it was perhaps the Revolutionary War that shaped who she would become as first lady.

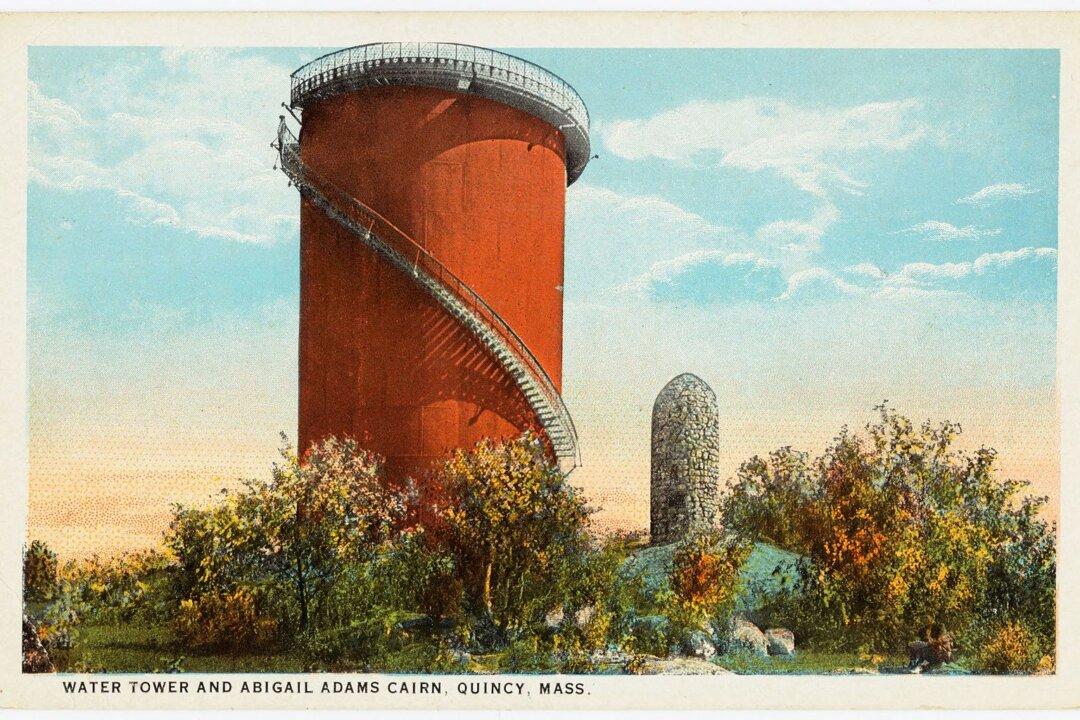

Described as a true partner to America’s first vice president and second president, Abigail was a proud Massachusetts native. Born in 1744, she married John Adams, raised her children, and died in the same colony-turned-state. She even named one of her children after the coastal Massachusetts city that would become her final resting place: Quincy. Abigail and John had six children—three daughters and three sons—and four of them lived to adulthood, with John Quincy Adams becoming the sixth U.S. president.