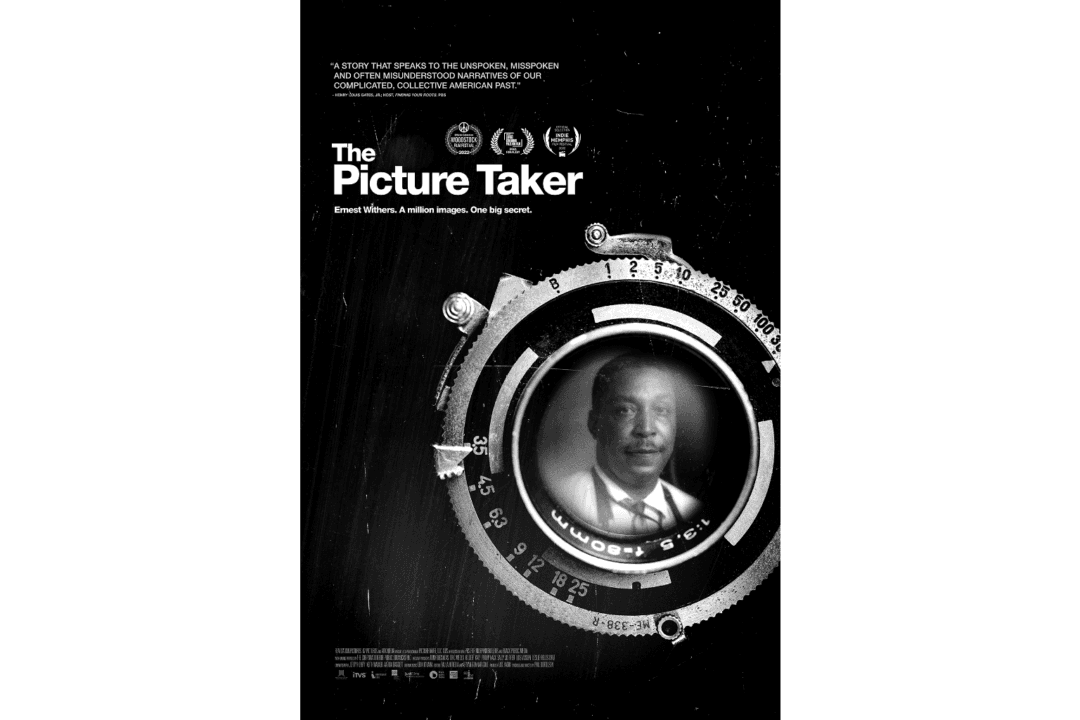

NR | 1h 20min | Documentary, History, Biography | 14 October (USA)

Born in 1922 in the Manassas section of Memphis, Tennessee, and dying in the same city in 2007, Ernest Withers led as full a life as anyone could possibly want or expect. He achieved national and international notoriety as a significant photojournalist.