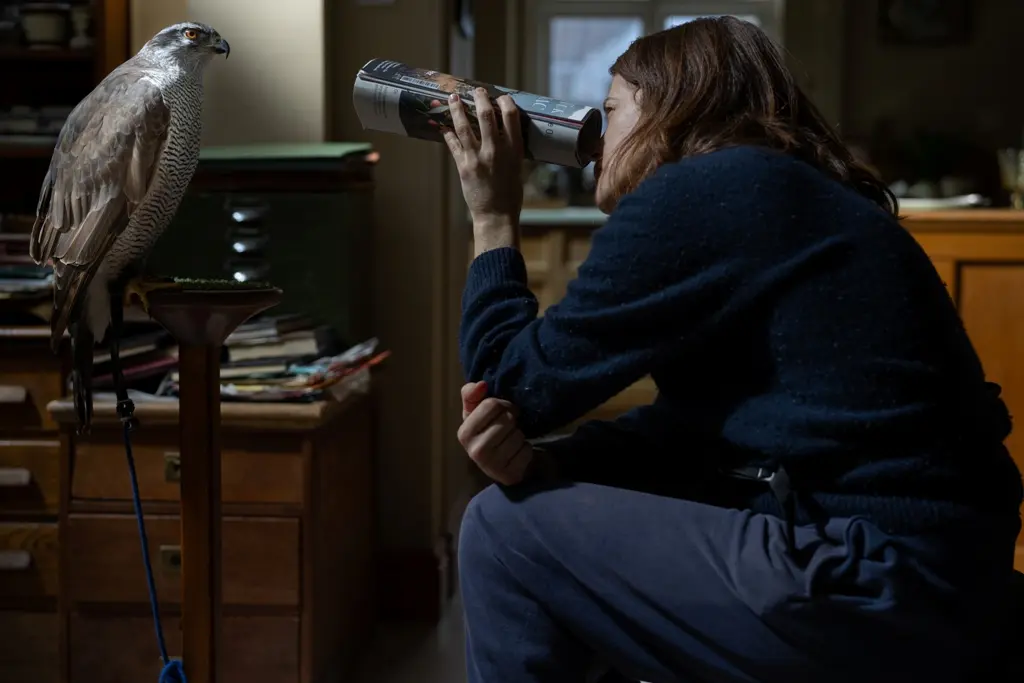

While watching “God’s Creatures,” I was reminded of a Billy Joel lyric and a line of dialogue from the movie “The Departed.” The Joel song “Through the Long Night” opens with “the cold hands, the sad eyes, the dark Irish silence.” In “The Departed,” Matt Damon’s character states “What [Sigmund] Freud said about the Irish is: We’re the only people who are impervious to psychoanalysis.”

|Updated:

Originally from the nation's capital, Michael Clark has provided film content to over 30 print and online media outlets. He co-founded the Atlanta Film Critics Circle in 2017 and is a weekly contributor to the Shannon Burke Show on FloridaManRadio.com. Since 1995, Clark has written over 5,000 movie reviews and film-related articles. He favors dark comedy, thrillers, and documentaries.

Author’s Selected Articles