Only the second feature from veteran TV director Miguel Sapochnik (“House,” “Game of Thrones”), “Finch” comes with a complicated back story. Initially titled “BIOS,” the spec (unsolicited) screenplay was penned by first-time writers Craig Luck and Ivor Powell. After a bidding war, it was bought by Steven Spielberg’s Amblin Entertainment and was going to be distributed by Universal. That was in 2017.

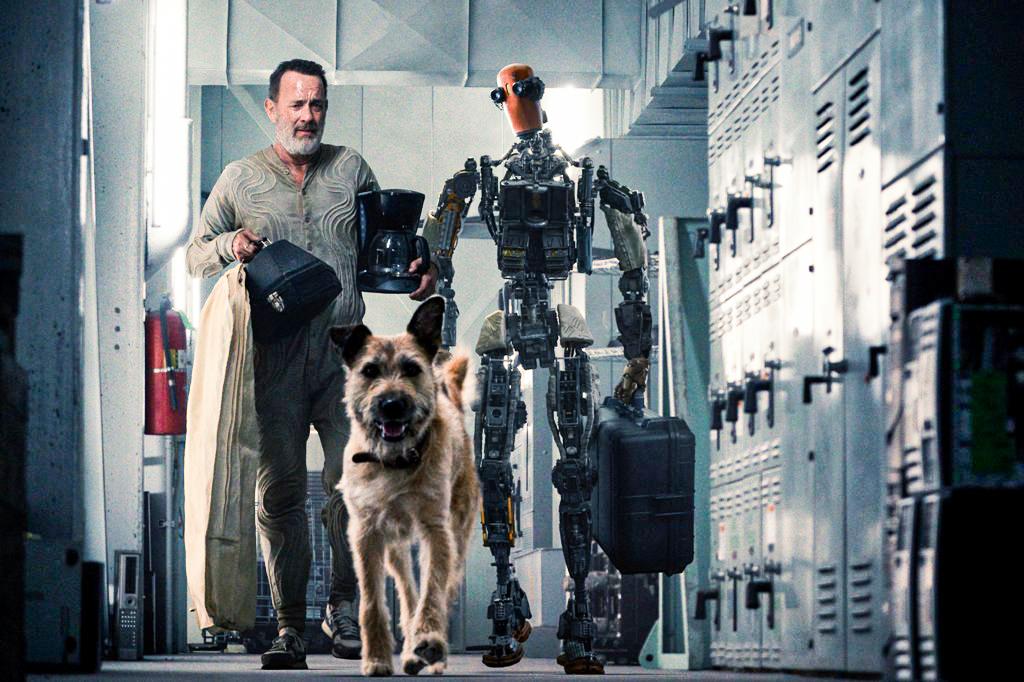

(L–R) Finch, Goodyear and Jeff (voiced by Caleb Landry Jones) in “Finch.” Columbia Pictures

|Updated:

Originally from the nation's capital, Michael Clark has provided film content to over 30 print and online media outlets. He co-founded the Atlanta Film Critics Circle in 2017 and is a weekly contributor to the Shannon Burke Show on FloridaManRadio.com. Since 1995, Clark has written over 5,000 movie reviews and film-related articles. He favors dark comedy, thrillers, and documentaries.

Author’s Selected Articles