Billed as “The First Latino Superhero Film” in its promotional materials, “El Chicano” debuted in theaters just this past weekend. The film comes at a time when Hispanics make up a large contingent of the domestic moviegoing audience, yet have only a small fraction of the speaking parts in those same films.

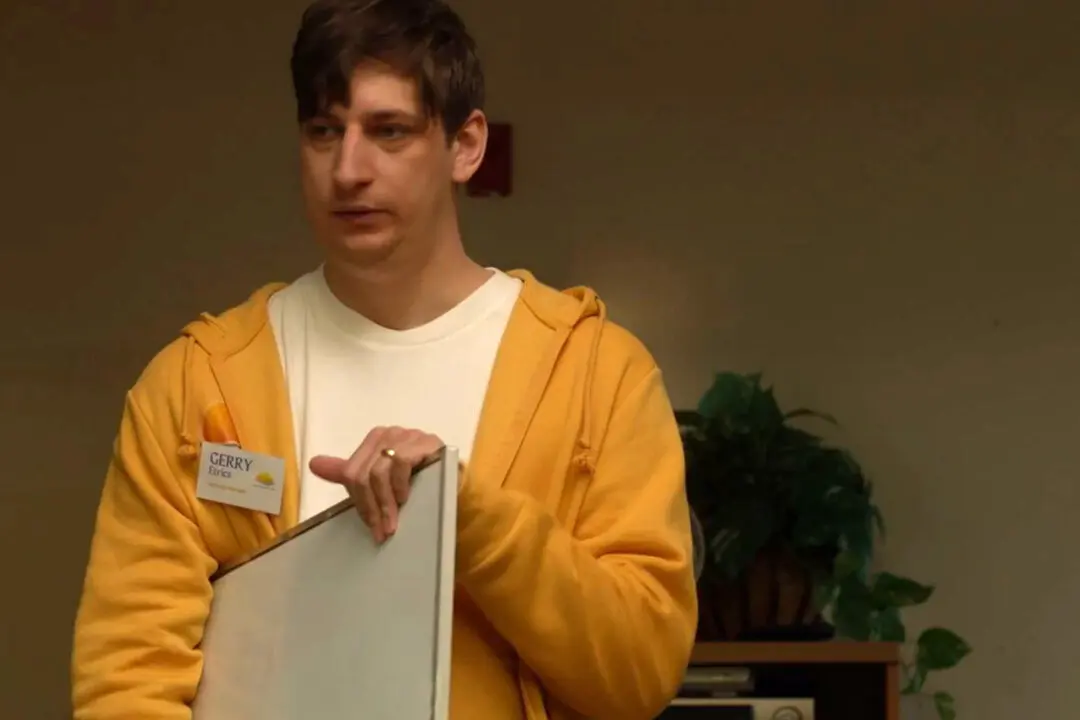

Raúl Castillo stars as the masked titular character in the film “El Chicano.” Briarcliff Entertainment