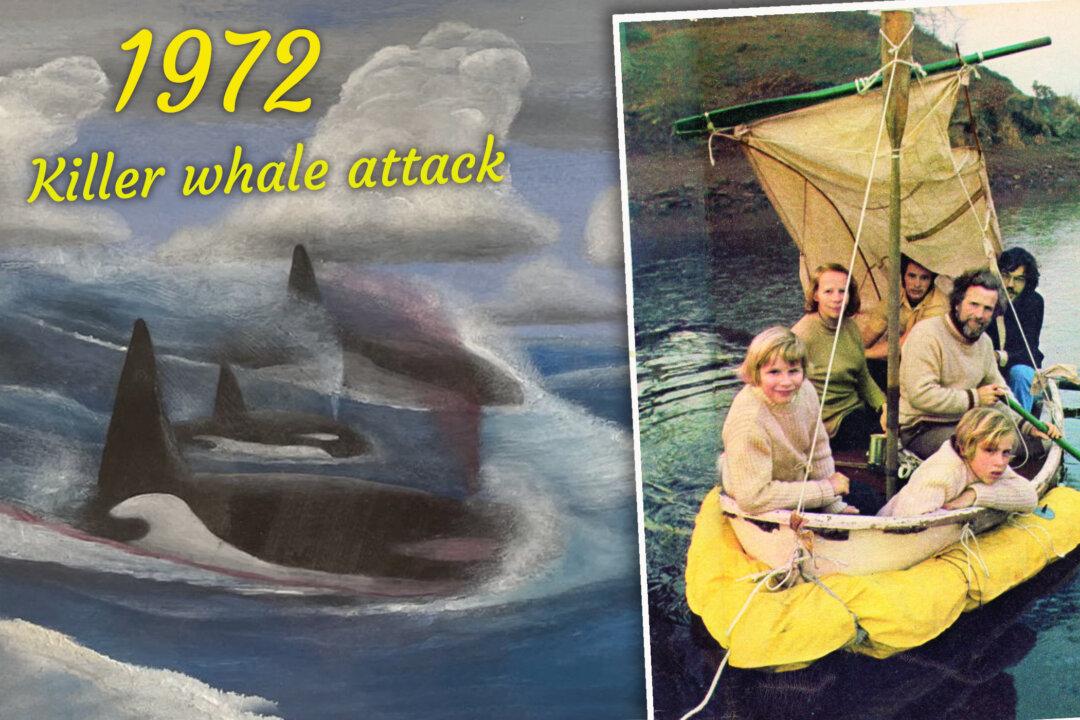

In 1972, a group of six, including children, got lost at sea after killer whales attacked their yacht. Adrift in the Pacific Ocean for 38 days with just a compass, they drank turtle blood to survive and learned to harvest rainwater amid pouring thunderstorms, all the while struggling to keep their damaged dinghy afloat.

It may seem like an almost unbelievable tale of daring, distress, and determination, but five decades after the fateful voyage, Douglas Robertson—one of the crew members who was just a teenager at the time—shared with The Epoch Times his vivid memories of surviving the shipwreck and the lessons learned. He says the unimaginable battle for life not only shaped his character but also led him to discover God amid all the chaos.