“Maestro,” Bradley Cooper’s biopic about Leonard Bernstein, is streaming on Netflix after a limited theatrical release in December 2023. Like its subject, “Maestro” is many things: a showcase for the acting talents of Mr. Cooper as Bernstein and of Carey Mulligan as his wife, Felicia; an insight into the cultural life of the 1940s to the 1970s; and a meditation on marriage. But at its core, “Maestro” is something far deeper. Mr. Cooper’s film is a devastatingly honest critique of the idea that traditions are disposable and that we as individuals have the power to transcend our own cultural norms to live solely for ourselves.

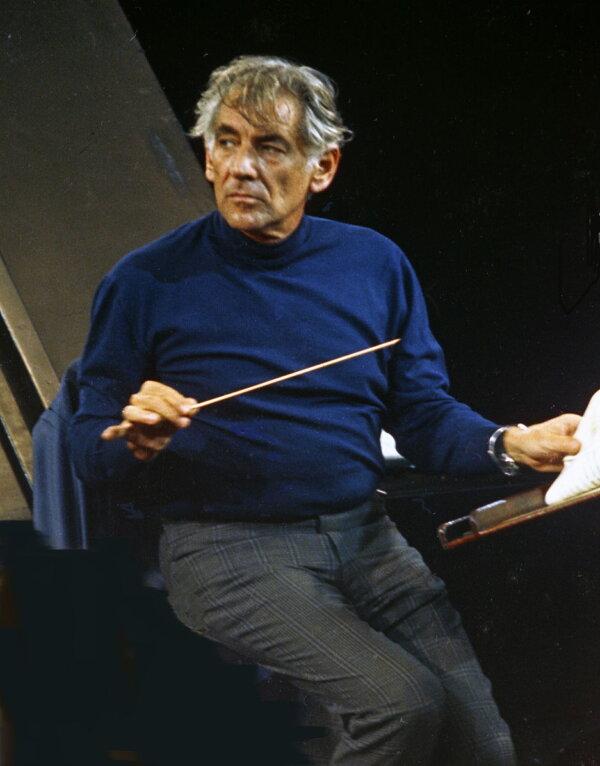

Leonard Bernstein conducting at the Royal Albert Hall in London, 1973. Allen Warren/CC BY-SA 3.0