It didn’t look like any other ruins—not at all. In fact, in some ways, as I walked through this maze, the place looked like the inhabitants never really left, despite the passage of thousands of years. Walls were painted with colorful frescoes, chambers filled with stone furniture and bowls and other day-to-day items. Red columns rose above the rubble of Europe’s oldest city, surrounded by staircases and colonnades and the remains of workshops and storage rooms, plus a complex system of drains and pipes that snaked across it all. Did things really look like this, back when the Minoans lived and worked here, as far back as 5,000 years ago? Probably not, exactly. But it’s a long story.

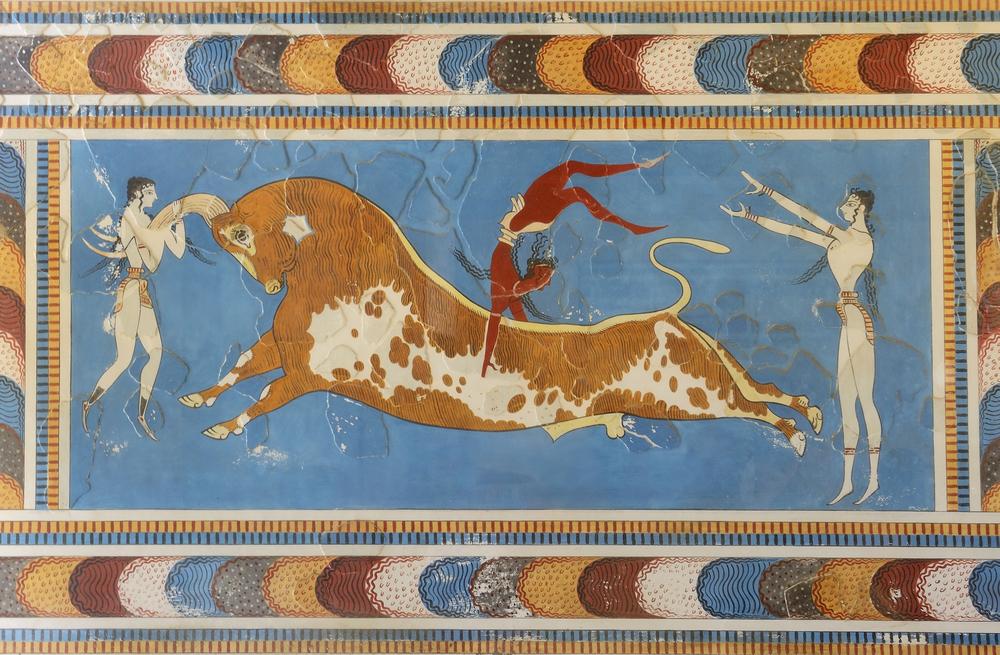

Bulls are often featured in frescoes at Knossos. Some say the layout of the palace suggests a labyrinth, as mentioned in the legend of the Minotaur. Pecold/Shutterstock