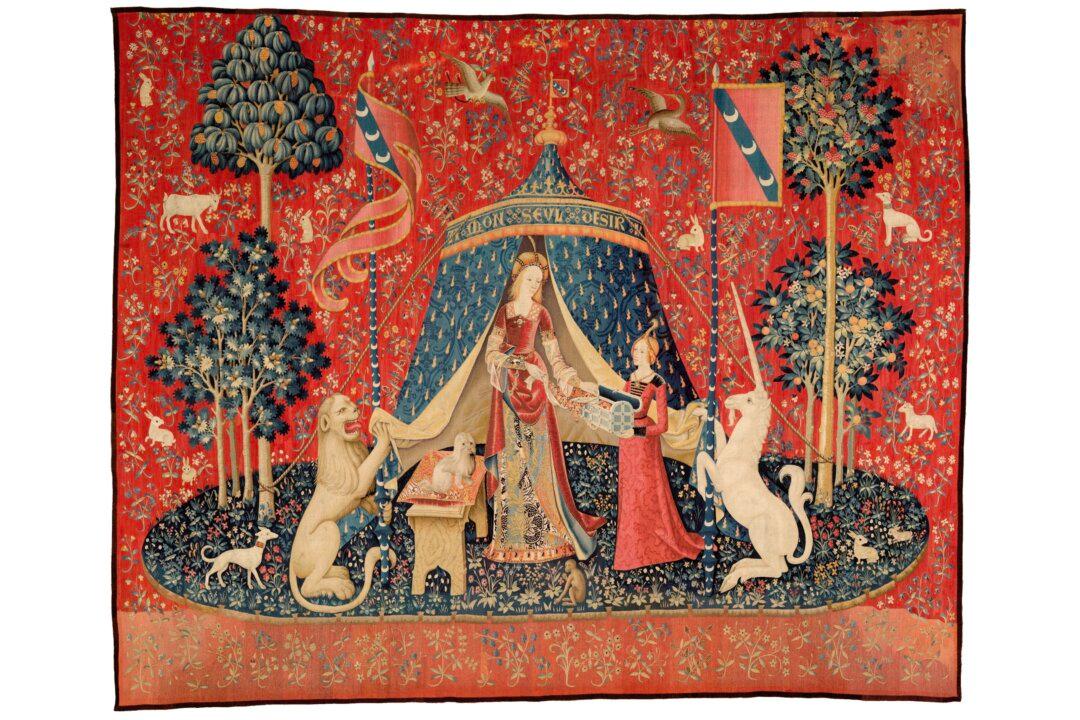

The arrival of “The Lady and the Unicorn” tapestry cycle at the Art Gallery of New South Wales in Australia from Feb. 10 presents a rare opportunity to see a work of art revered by specialists and enthusiasts alike. It has been called everything from the “Mona Lisa of the Middle Ages” to “a national treasure of France.”

Comprising six individual pieces, the tapestry cycle was made around the year 1500. Tapestries of such quality are rare, and few examples survive.