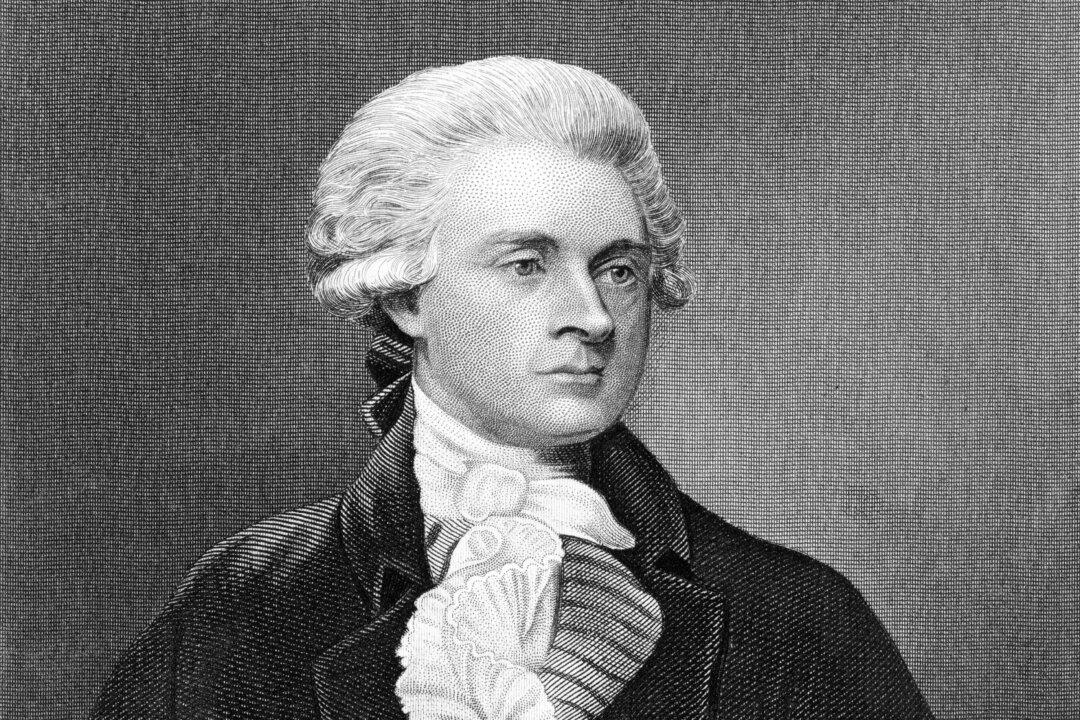

After the British burned the congressional library during the War of 1812, former president Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826) sold his personal library of some 6,500 books to Congress, which for years they served as the heart of the Library of Congress’s collection. Later he wrote to his correspondent and friend John Adams, “I cannot live without books, but fewer will suffice where amusement, and not use, is the only future object.”

A fire had destroyed Jefferson’s first personal collection of books in 1770. After making the sale of his second collection to Congress, he began putting together a third library, amassing about 1,600 volumes before his death in 1826.