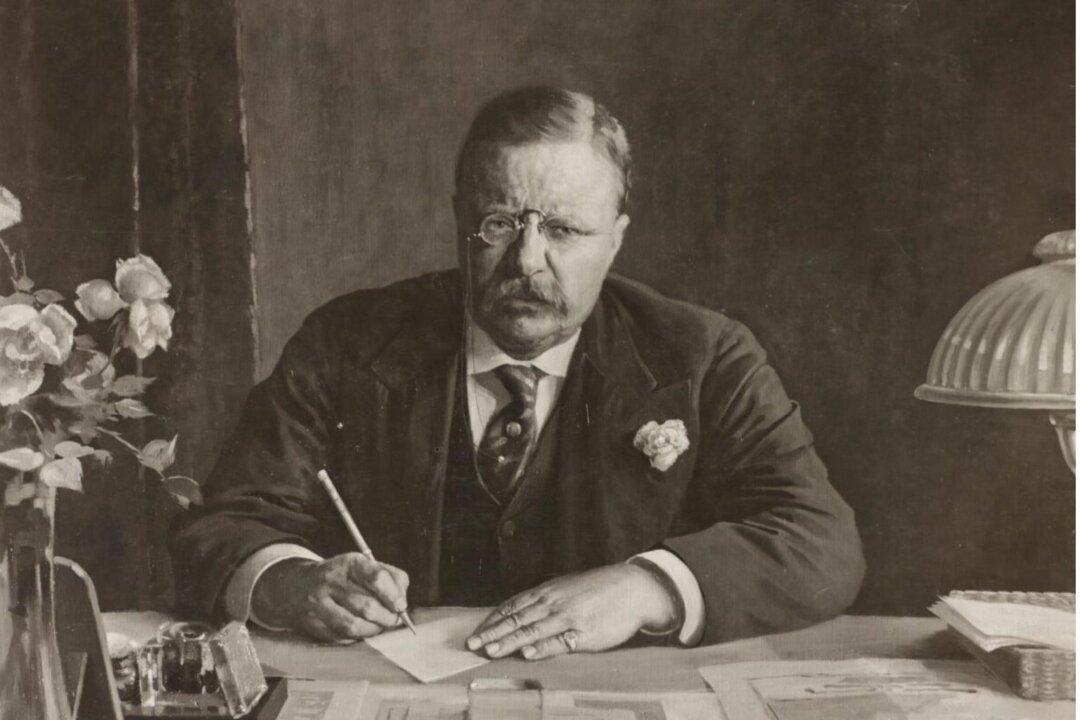

Of all our U.S. presidents, Theodore Roosevelt hands down wins the title of “Most Voracious Reader.”

A skilled speed-reader, he frequently consumed a book before breakfast and ingested one or two more in the evenings. By his own estimate, this reader of libraries had made his way through tens of thousands of books, including several hundred in foreign languages.