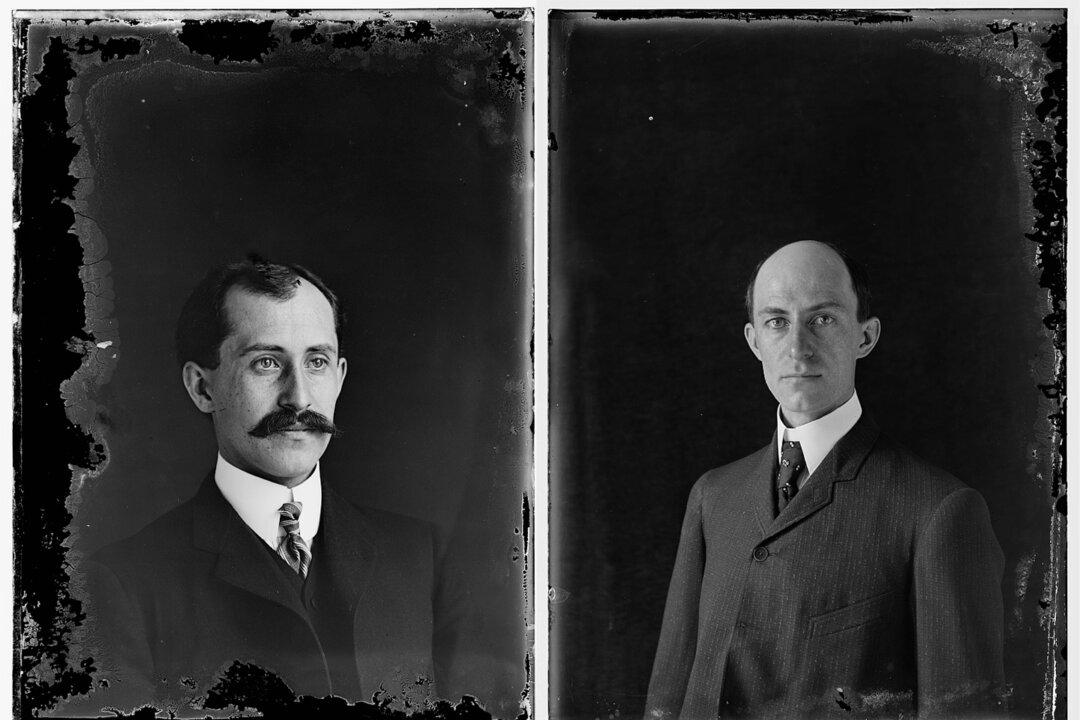

On Dec. 17, 1903, brothers Wilbur and Orville Wright each made two flights using a heavier-than-air machine on the sandy beach of Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. The longest of these flights lasted 59 seconds.

Not quite 66 years later, astronauts walked on the moon.