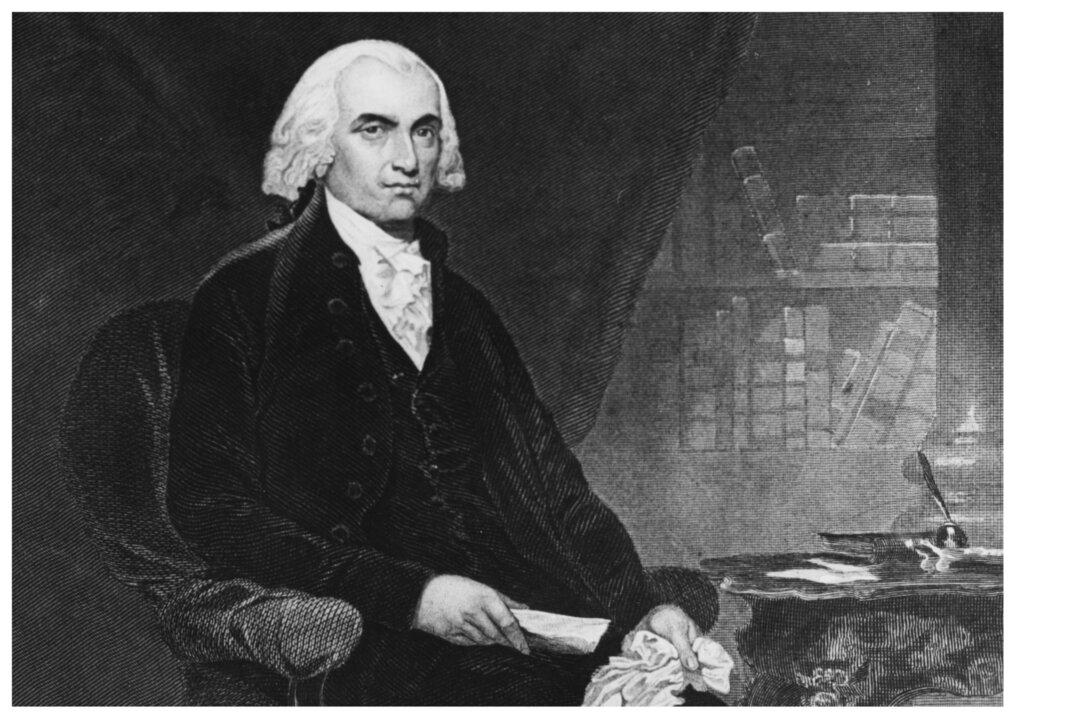

James Madison (1751–1836) was a small man—at 5 feet 4 inches our shortest president—frail, often sickly, shy, and modest about his abilities and achievements. He never commanded troops in battle like George Washington or waged a war of wits in the courtroom as John Adams had.

Yet his predecessor in the White House, Thomas Jefferson, dubbed Madison “the greatest man in the world.” John Adams wrote to Jefferson regarding Madison that “his Administration has acquired more glory, and established more Union, than all his three Predecessors Washington Adams and Jefferson put together.” Given that Adams was one of these predecessors, that was indeed high praise.