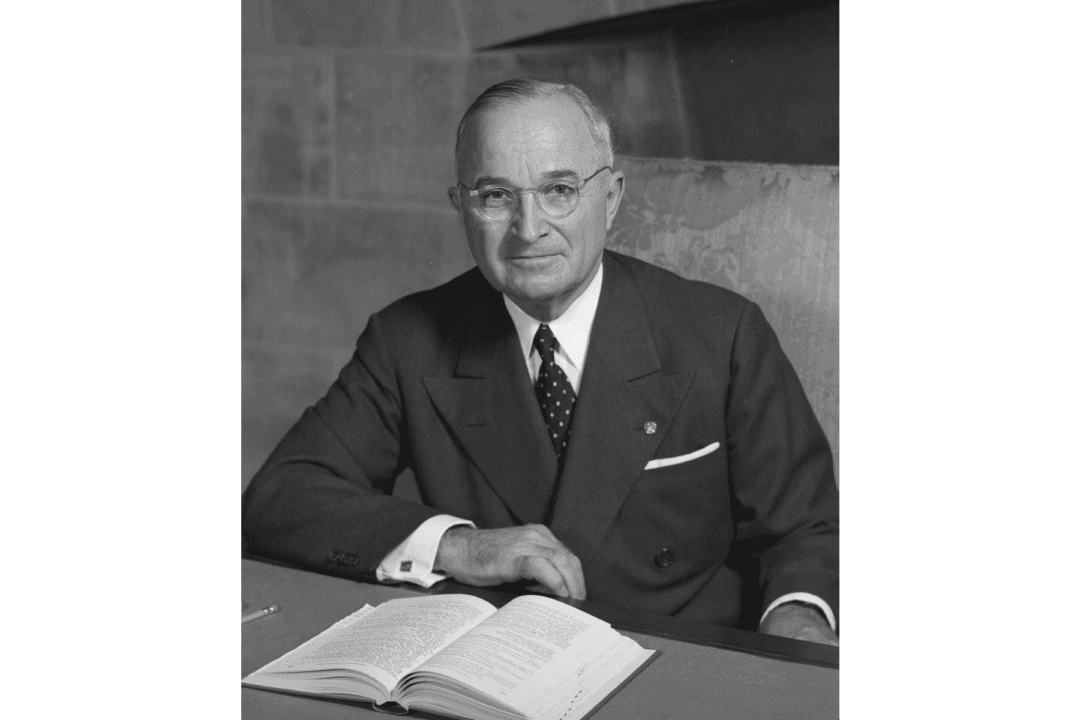

With the death of Franklin Roosevelt on April 12, 1945, Harry Truman (1884–1972) became America’s 33rd president. For the next seven years, he was caught up in swirl of momentous events.

He oversaw the ending of the war in Europe, authorized the atomic bombings on Japan, guided the country from a wartime to a peacetime economy, faced the international challenges brought on by the Cold War with Russia, helped institute the Marshall Plan, recognized the new state of Israel, and dispatched military forces to defend South Korea from a communist invasion.