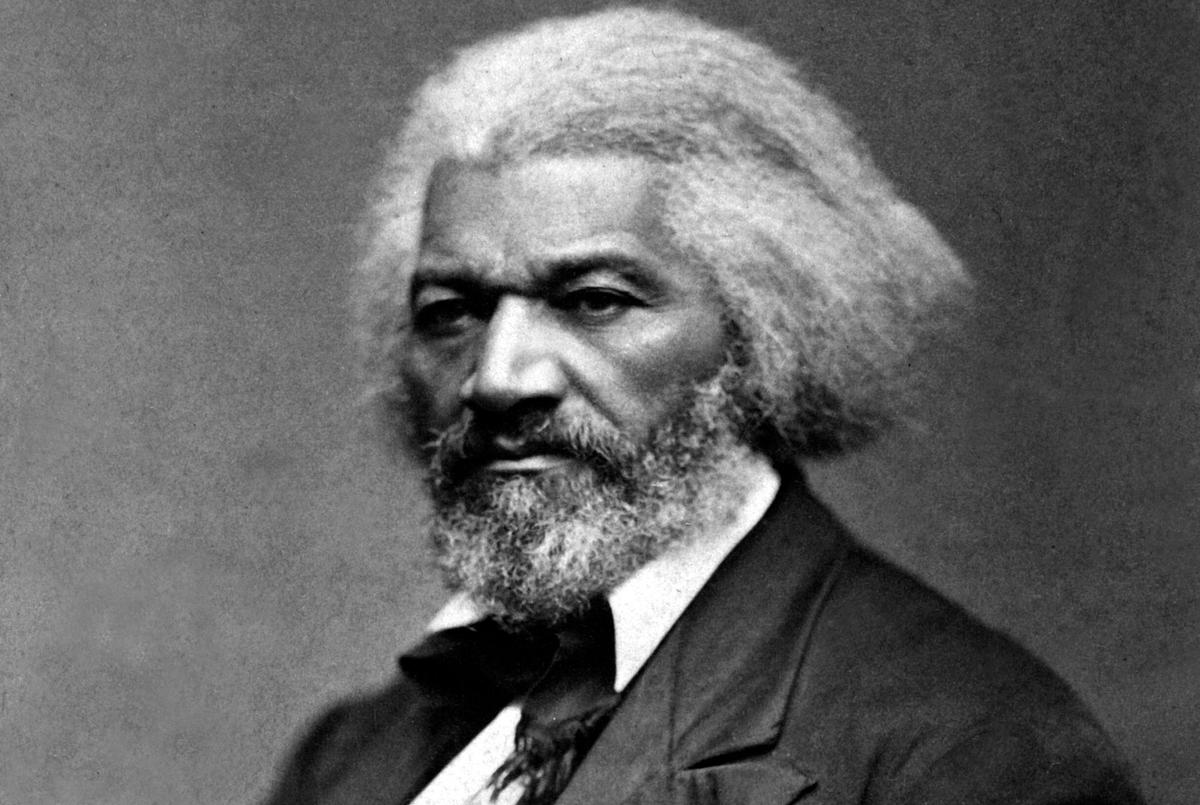

Frederick Douglass (1818–1895) was born into slavery in Eastern Maryland. His 1845 autobiography “Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Written by Himself,” recounts his years of bondage and daring escape north in 1838, though he omitted many details to protect those who had given him help. The book quickly found a large audience, making Douglass a popular public speaker in abolitionist circles. It remains an American classic.

Frederick Douglass, circa 1879. National Archives and Records Administration. Public Domain