Son of an active duty soldier, Douglas MacArthur (1880–1964) grew up on military posts and then spent 52 years in uniform. Praised by admirers as a military genius and criticized by detractors as a narcissistic dilettante, he won high honors during his time as a cadet at West Point, commanded troops in combat during World War I, was chief of staff under presidents Herbert Hoover and Franklin Roosevelt, and helped lead America to victory against Japanese imperial forces during World War II.

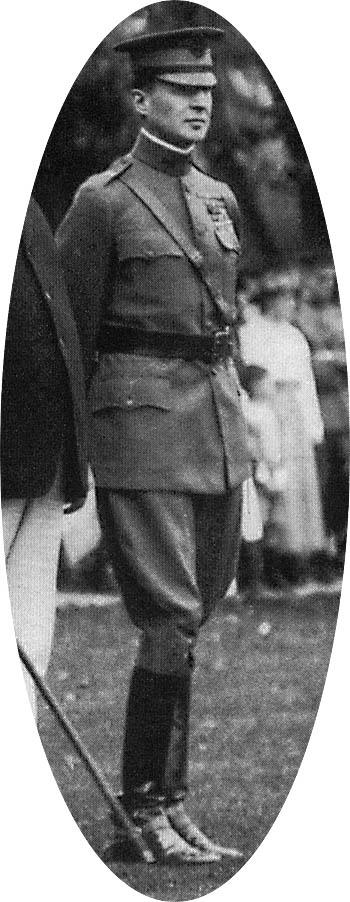

Douglas MacArthur as West Point superintendent. Public Domain