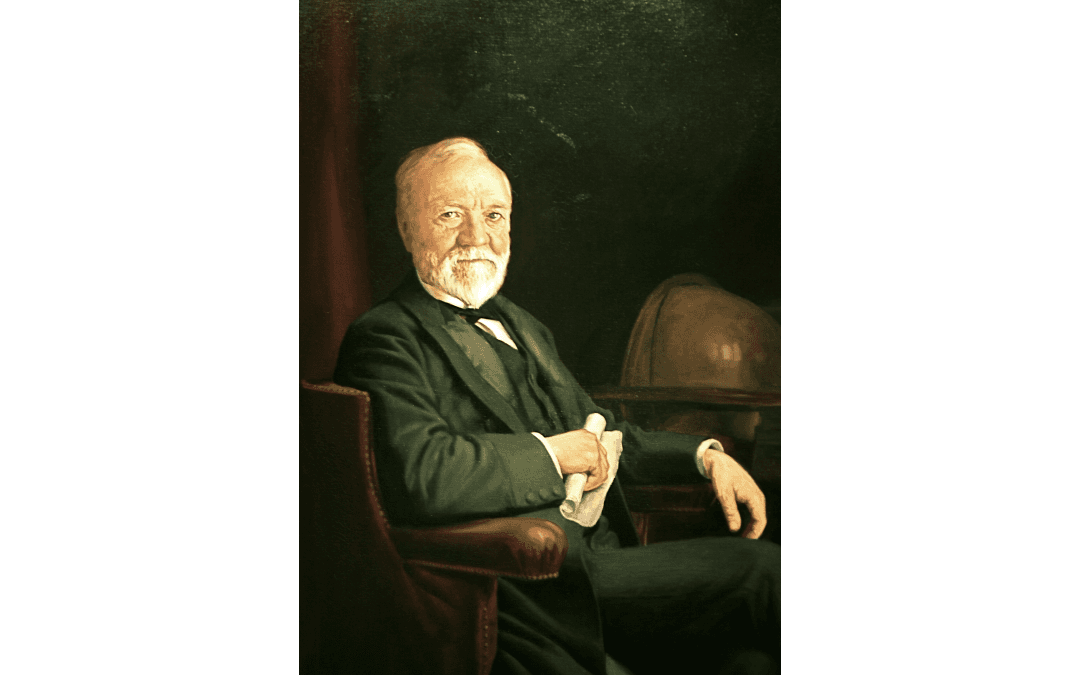

At age 13, newly arrived Scots immigrant Andrew Carnegie (1835–1919) first worked 12-hour days earning $1.20 a week as a bobbin boy at a Pennsylvania cotton mill. By dint of his drive, a keen mind, and an eye for opportunity, he improved his lot by becoming a messenger boy. His abilities and ambition soon made him a telegraph operator, then a superintendent for the Pennsylvania Railroad. By 30, Carnegie was rich, an investor in the ironworks industry and other enterprises, and was fast becoming a major player in steel production. When he sold Carnegie Steel to J.P. Morgan in 1901, Carnegie retired from business as the wealthiest man in the world.

During Carnegie’s time as a teenage messenger, a local entrepreneur, Col. James Anderson, made his private library available on Saturdays for use and borrowing privileges to working-class boys. Writing later about the consequences of this generosity, Carnegie observed that in this way “the windows were opened in the walls of my dungeon through which the light of knowledge streamed in.” In his “Autobiography,” Carnegie paid this tribute to Anderson, “To him I owe a taste for literature which I would not exchange for all the millions that were ever amassed by man. Life would be quite intolerable without it.”