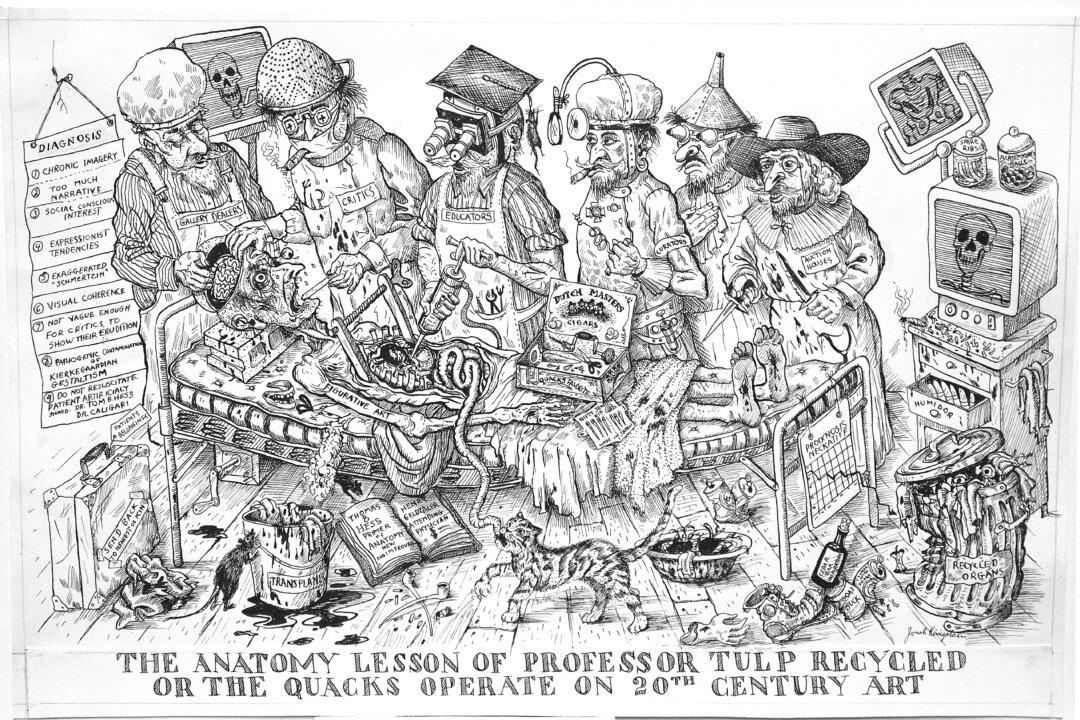

NEW YORK—In one of his editorial-style cartoons, artist Jonah Kinigstein likens today’s art world to a game of baseball in which all the rules have been removed. A caricature of Marcel Duchamp, who in 1917 signed a urinal and called it art, squats at second base in front of a sign that reads “Up to Date Museum: Nothing older than 15 minutes accepted.”

In another, some cyborg-harpies—the demons of the avant-garde—gather menacingly around a nude woman who symbolizes figurative art.

Kinigstein’s blunt, darkly drawn, and image-packed pictorial metaphors are the subject of a new show at the Society of Illustrators titled The Emperor’s New Clothes curated by Gary Groth. Critics of the modern art world use The Hans Christian Andersen tale to describe the public’s reluctance to admit that they don’t “get” or simply don’t care for modern and conceptual art, though media tells them they should.

With this series of drawings, Kinigstein has put himself in the position of the child who points out the obvious—that the emperor is naked. Usually in life, the obvious doesn’t bear repeating with as much vehemence as is shown in Kinigstein’s cartoons. But seeing Kinigstein’s cartoons offers some catharsis—but maybe only if you’re already of the persuasion that modern art has little merit.