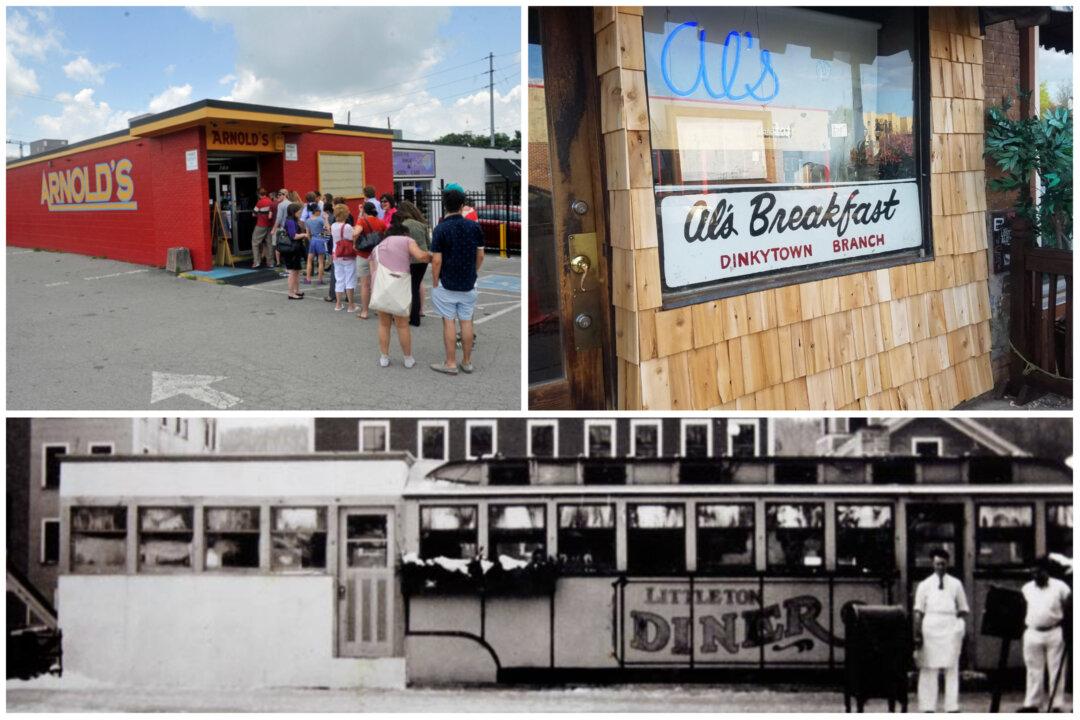

Mom and pop restaurants were once ubiquitous in the United States. Whether you lived in a large city such as Minneapolis, a medium-sized city such as Nashville, or a New Hampshire village, there was a little restaurant where you could get homestyle cooking at an affordable price—all while connecting with the community.

When a beloved community restaurant closes, something important is lost. These are the places where Americans make memories, livelihoods, and lifelong friendships. The meals themselves often reflect regional culinary traditions. And their owners are living their respective versions of the American dream.