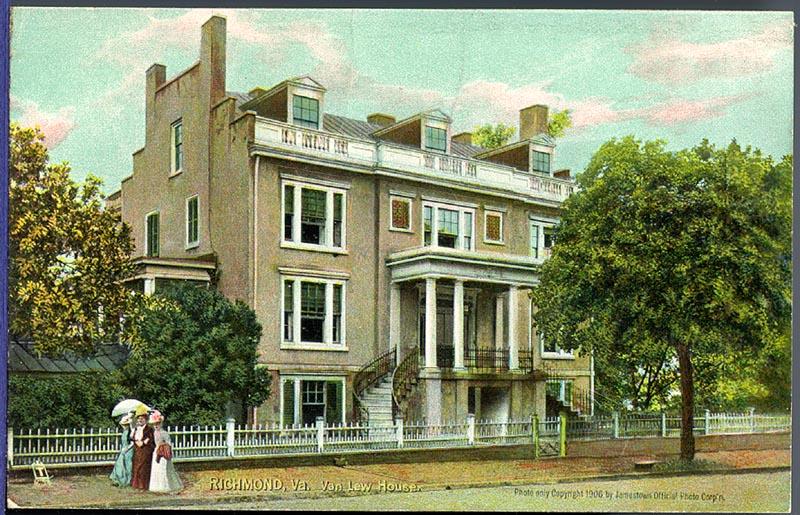

Elizabeth Van Lew (1818–1900) was born in Richmond, Virginia’s capitol, though both of her parents had northern roots. Her father, John Van Lew, was from Long Island, New York, and her mother, Eliza Louise Baker, was from Philadelphia. The family was part of Richmond’s high society, living in a mansion within the prominent Church Hill neighborhood.

Van Lew began her education in Richmond, but finished at a Quaker school in Philadelphia. Pennsylvania was founded by the Quaker Englishman William Penn. The Quakers possessed pacifist and anti-slavery sentiments, and the latter indeed influenced Van Lew’s views—views she shared with her mother. Although the Van Lews owned more than 20 slaves, Van Lew and her mother often used the manumission process to free their slaves or enable them to live as if they were free. One of the Van Lews’ slaves, Mary Jane Richards, who was manumitted, was educated in either Philadelphia or Princeton, and then she left for Liberia in 1855 as a missionary to join the American Colonization Society.