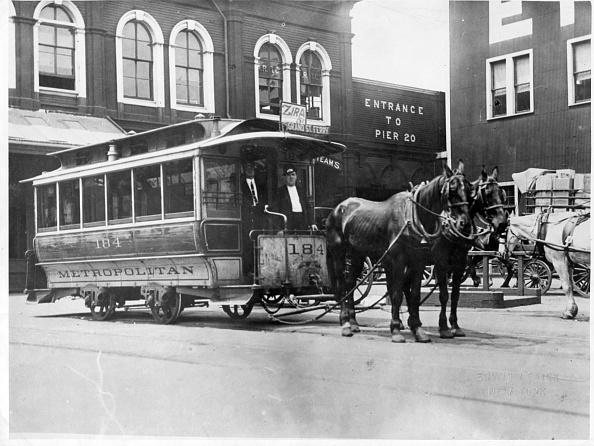

Well before Rosa Parks, Elizabeth Jennings Graham also refused to give up her seat on public transportation that was denied her due to her skin color. The actions of the free African American school teacher, also known as the “Nineteenth-Century Rosa Parks” would lead to the desegregation of the New York City streetcar system.

Graham was born in 1827 to prominent middle-class African American parents Thomas Jennings and Elizabeth Cartwright. Graham’s father was a successful tailor. In 1821, he was awarded a patent for developing a new dry cleaning method.