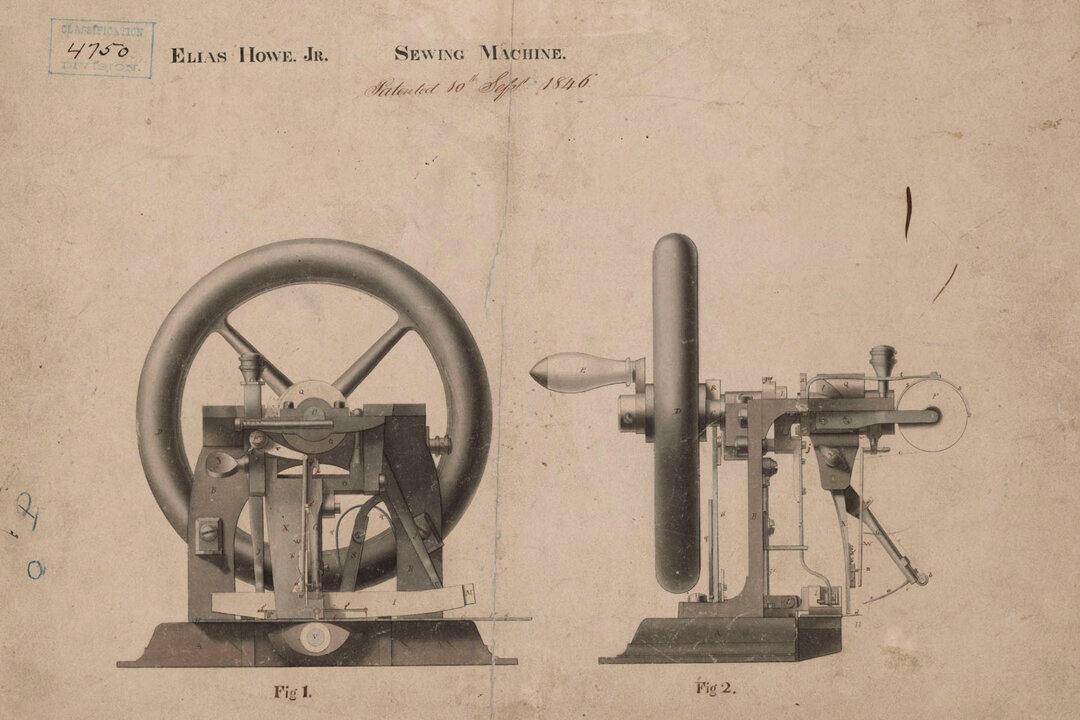

In this installment of ‘Profiles in History,’ a young, sickly inventor creates a machine that ‘altered the course of contemporary civilization.’

Elias Howe Jr. (1819–1867) was born on a farm near the small Massachusetts town of Spencer. By the time he reached 16, he had decided to leave the farm life and move north to Lowell. Howe was born lame that made manual labor, such as farming, difficult to do. This may have been part of the reason for moving.