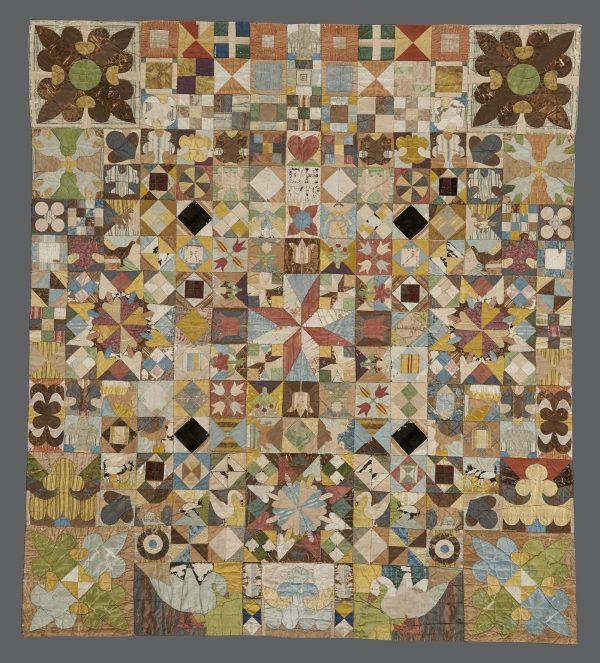

Meet the 300-year-old coverlet that is surprisingly full of color and has a little mystery to its history. Made in 1718, it is the oldest dated patchwork coverlet in the UK. Celebrating its birthday at the American Museum in Britain, in Bath, England, this piece of cloth is not hiding in a dusty closet; its vibrancy is displayed center stage in the folk art gallery of the museum.

The 1718 silk patchwork coverlet. American Museum in Britain