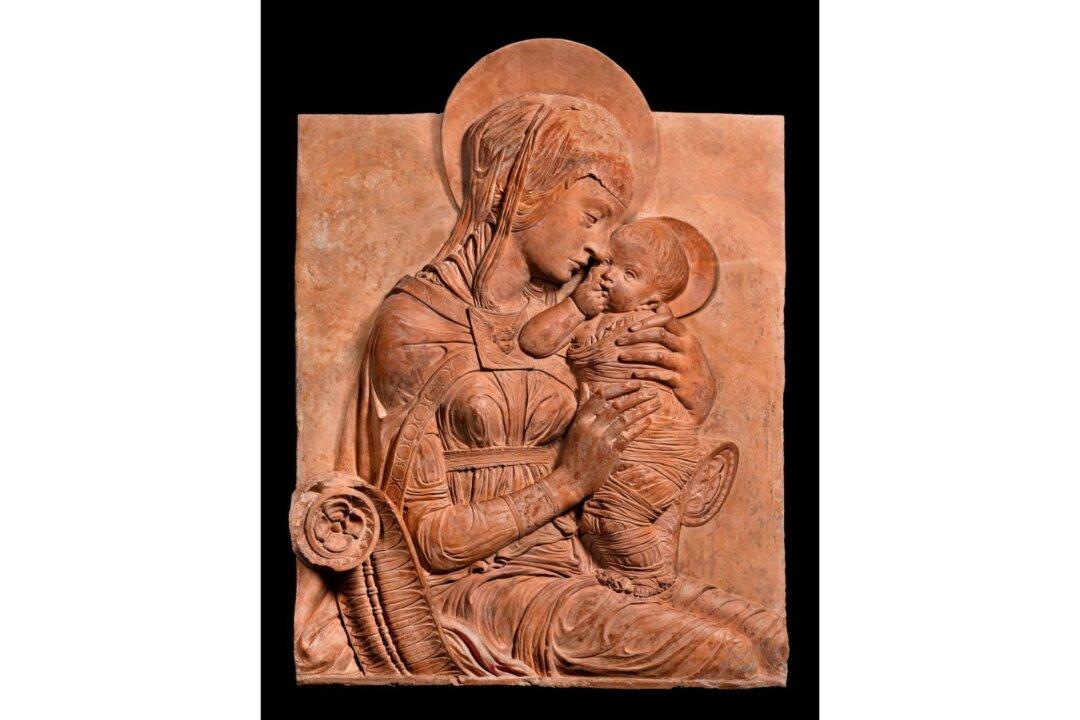

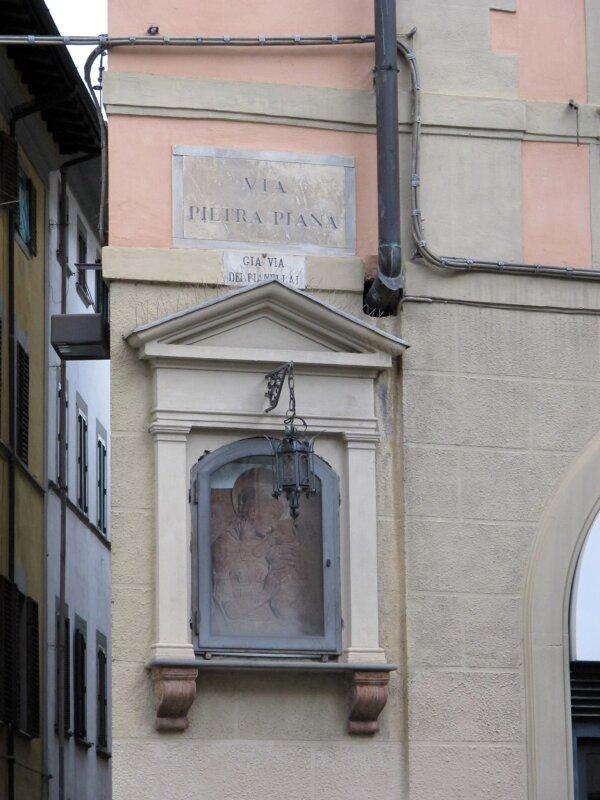

For centuries, Donatello’s “Madonna of Via Pietrapiana” has been hidden in plain sight in the center of Florence. Experts had long believed a follower of the Italian master had created the terracotta bas-relief that was hung high in a tabernacle frame under a street sign on a villa at the address Via Pietrapiana 38. But in 1985, after the work had been restored, writer and art historian Charles Avery attributed the obscure relief to Donatello, as an autographed work. It was the master’s last privately owned work.

For centuries, one of Donatello’s terracotta madonnas was hung high on an unassuming villa in Florence, Italy. In this image taken in 2013, we can see the early Renaissance master’s “Madonna of Via Pietrapiana” under the street sign it's named after. Sailko/CC SA-BY 3.0 DEED