Does money buy high public office? It’s a contentious political question. The best answer, it seems to me, is this: Sometimes it does and sometimes it doesn’t. Just ask presidential hopefuls Jeb Bush and Michael Bloomberg.

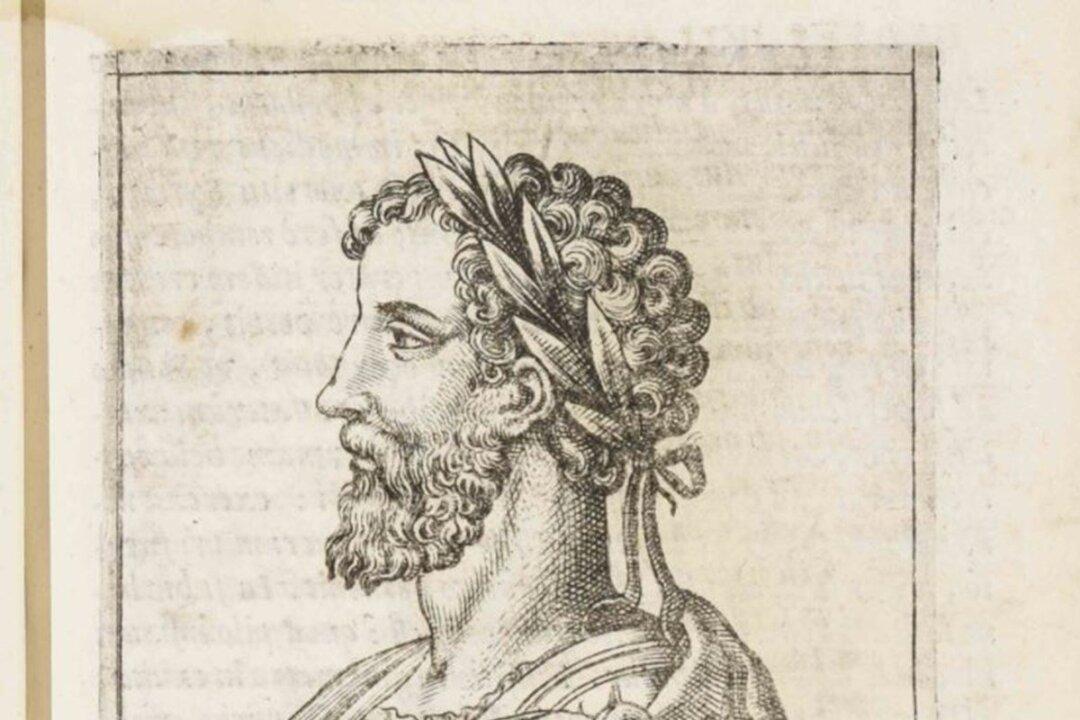

One occasion when money bought the highest office in the land—in plain public view—occurred in 193 A.D. in ancient Rome. The position of Emperor of the Roman Empire was auctioned off and the winning bid belonged to a man named Didius Julianus. Here’s the remarkable story.