We talk of death as if it were a part of life, but it’s not. As philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein observed, “Death is not an event of life. Death is not lived through.”

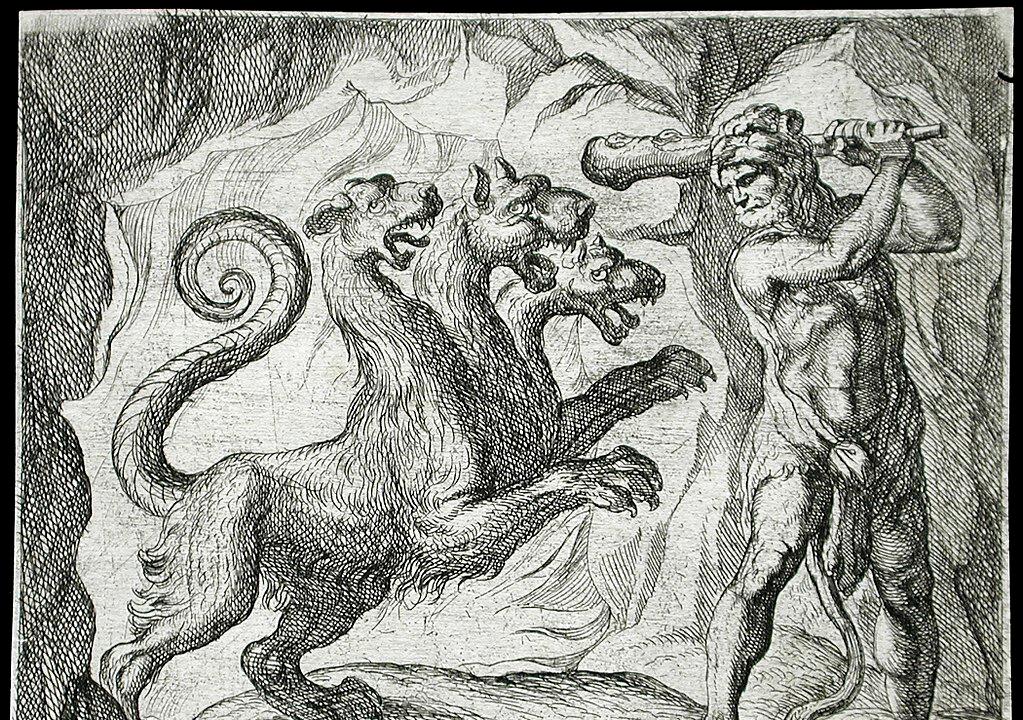

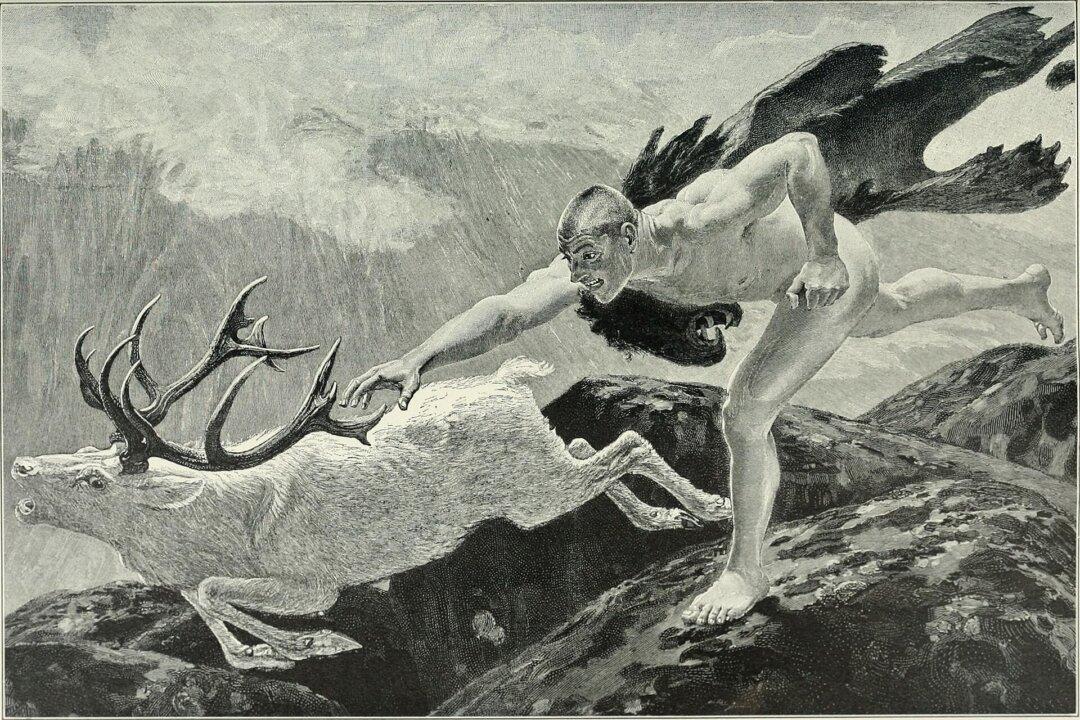

In talking about death, we must resort to metaphors—one often used is the “realm” of the dead, a place that is a kingdom. For every kingdom there is a king, which, in Greek mythology, is Hades. Hades is used to refer both to the place of the dead and the king of the dead, the brother of the supreme god, Zeus.