Sir Walter Raleigh (circa 1552–1618) sat for 48 portraits in his lifetime, a figure that reveals both a flourishing ego and a patience uncharacteristic of the man. Yet whenever Raleigh comes to mind, I don’t think of those paintings but of the actor Errol Flynn. Star of such movies as “The Adventures of Robin Hood,” “The Sea Hawk,” and “The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex,” Flynn brought to his characters gallantry, daring, wit, and dash. Put him in front of a camera, and the effect was electric. Throughout his life, both in and out of the English court, Raleigh displayed this same vibrancy.

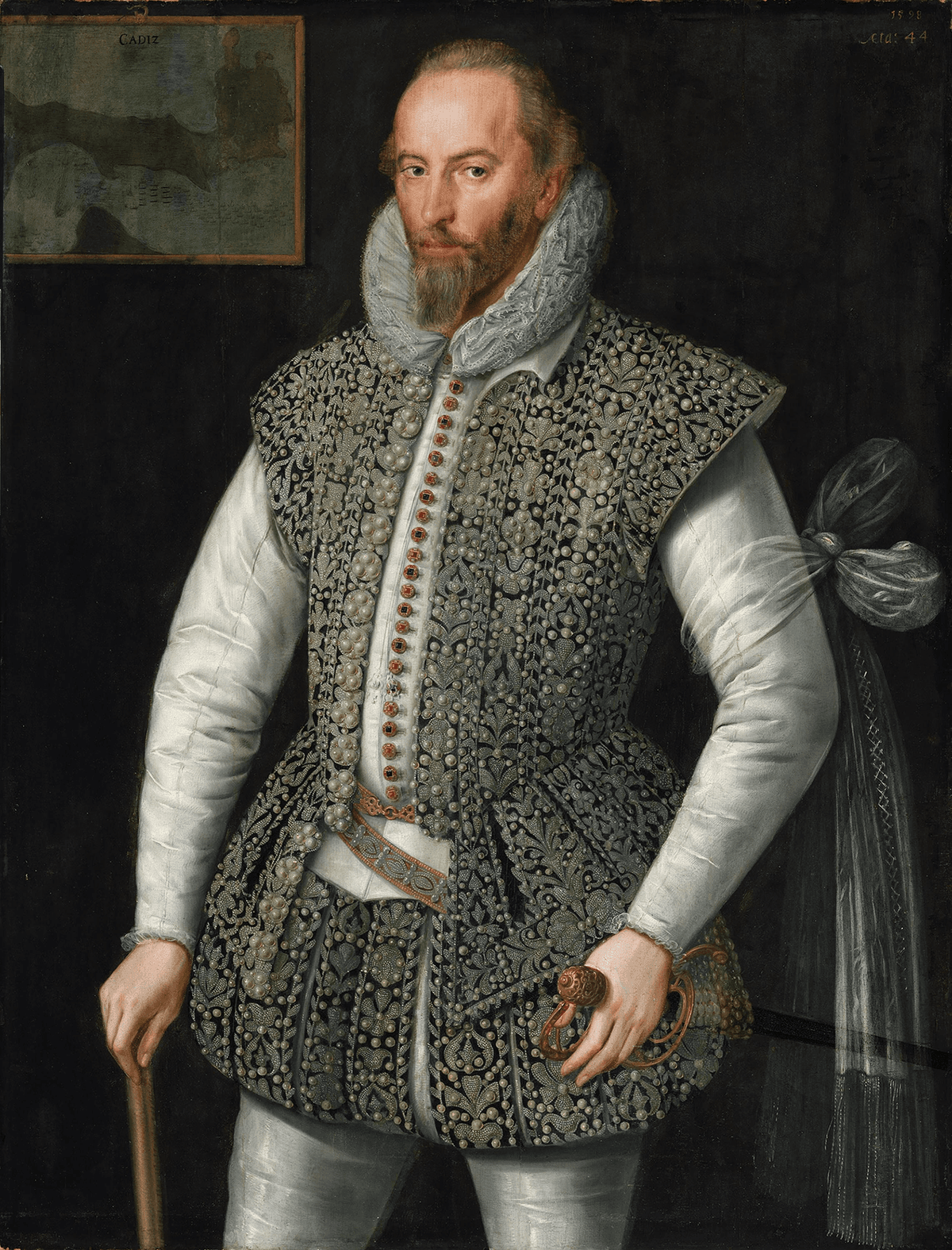

"Sir Walter Raleigh," 1598, by William Segar. Oil on canvas. National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin. Public Domain